At the time of his death in 1790, Benjamin Franklin was world-famous as a philosopher, scientist, inventor and diplomat. His significant contributions to the American Enlightenment and as a leading figure of the Revolution of 1776 are far too numerous and important to be appropriately dealt with in this short space. However, his work as a printer deserves special appreciation.

At the time of his death in 1790, Benjamin Franklin was world-famous as a philosopher, scientist, inventor and diplomat. His significant contributions to the American Enlightenment and as a leading figure of the Revolution of 1776 are far too numerous and important to be appropriately dealt with in this short space. However, his work as a printer deserves special appreciation.

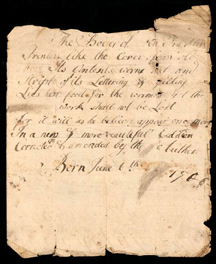

In 1728, when he was 22 years old, Benjamin Franklin wrote the following humorous epitaph for himself:

The body of

B. Franklin, Printer

(Like the Cover of an Old Book

Its Contents torn Out

And Stript of its Lettering and Gilding)

Lies Here, Food for Worms.

But the Work shall not be Lost;

For it will (as he Believ’d) Appear once More

In a New and More Elegant Edition

Revised and Corrected

By the Author.

In his last will and testament of 1788, Franklin amended his plan for the inscription on his gravestone to bear just the names of himself and his wife—Deborah Read Franklin—who preceded him in death by 15 years. In his will, however, he identified himself thus: “I, Benjamin Franklin, of Philadelphia, printer …”

In his last will and testament of 1788, Franklin amended his plan for the inscription on his gravestone to bear just the names of himself and his wife—Deborah Read Franklin—who preceded him in death by 15 years. In his will, however, he identified himself thus: “I, Benjamin Franklin, of Philadelphia, printer …”

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin was the last of his father’s seventeen children. Franklin began his printing career when he was apprenticed to his brother, James Franklin, at age twelve. After he was denied his wish to be published in James’ newspaper, the young Ben began submitting letters to The New-England Courant under the pseudonym “Mrs. Silence Dogood.” The correspondence became very popular in the local community.

At age 17, Benjamin left his apprenticeship without permission, ran away to Philadelphia to start out on his own. After building his reputation as a skilled craftsmen—as both a type compositor and pressmen—and disciplined worker, Franklin had the opportunity to set up a printing house in partnership with Hugh Meredith in 1728. The following year he became publisher of The Pennsylvania Gazette, one of two newspapers in the colonies.

In his Philadelphia printing shop, Franklin produced his newspaper, government printing projects and he took on a considerable volume of print for hire such as forms, lottery tickets, handbills and bookwork. Beginning in 1730, Franklin was printer of all paper money issued by Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware.

Perhaps one of his most recognized projects was “Poor Richards’s Almanack,” which Franklin wrote under the pseudonym Richard Saunders and printed for 25 years beginning in 1732. As Franklin explained in his Autobiography, “I endeavor’d to make it both entertaining and useful, and it accordingly came to be in such Demand that I reap’d considerable Profit from it, vending annually near ten Thousand. . . . I consider’d it as a proper Vehicle for conveying Instruction among the common People, who bought scarcely any other Books.”

Although Franklin was not the author of the many clever aphorisms contained the Almanack, it can be argued that these sayings have been passed down and are part of our speech today because of his work. Here are a few of them:

– Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy wealthy and wise. (1735)

– The rotten apple spoils his companion. (1736)

– No gains without pains. (1745)

During his printing career, Ben Franklin made important contributions to the technology and practice of printing. He made major improvements to printing press design and helped to set up paper mills in the south. He established in 1778 the first printers’ association in America (later named the Franklin Society), established the first public library, is credited with the idea for the first American magazine and was appointed the first Postmaster by the Second Continental Congress in 1775. Benjamin Franklin created a franchise business model that launched two-dozen printing establishments up and down the Atlantic Coast.

In his “Apology for Printers,” Franklin elaborated a philosophy for the role of the printer in modern society: “Printers are educated in the Belief, that when Men differ in Opinion, both Sides ought equally to have the Advantage of being heard by the Publick; and that when Truth and Error have fair Play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter.” If printers printed only what they believed, “the World would afterwards have nothing to read but what happen’d to be the Opinions of Printers.”

We look back and appreciate the work of Benjamin Franklin with pride; he was one of our own.