Some readers are likely wondering: why take so much time and space reviewing the work of individuals in the history of print media? What does this have to do with the printing business and the challenges we face right now, especially with media technology in transition and in a difficult economy? These are valid questions.

Although the effort requires bookwork and more than a casual reading of Wikipedia entries, it is not an academic exercise or something of interest only to print technophiles. Appreciation for the major transformations of the past provides a guide for navigating contemporary problems; it also assists in charting a path to the uncertain future.

Business decisions are influenced by multiple and complex factors. Availability of financial and human resources, technology development, market trends, customer needs, competition and risk-reward calculations all shape judgments about what should or should not be done. Knowledge of the rich history of the printing industry reveals the rhythmic relationship between the present and the past. Thereby, it is an indispensable tool for business thinking and planning.

The period of printing history under review is perhaps more resonant with our own time than at any other in the 570 years since Gutenberg. At the turn of the nineteenth century, a fundamental transition began: press technology went from wood and hand power to iron and steam power; during the years 1800-1814 all of the basic elements for the transformation of print from a craft to an industry were in place.

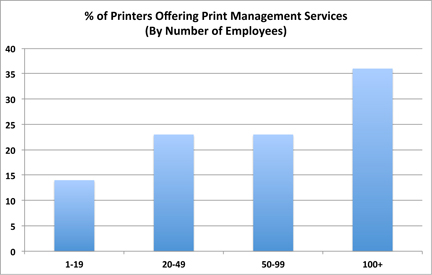

A measure of the magnitude of this revolution is the ten-fold increase in press productivity in the first two decades of the nineteenth century:

Up to 1800 1800 1818

Press technology Gutenberg Stanhope Koenig

Sheets per hour 240 480 2400

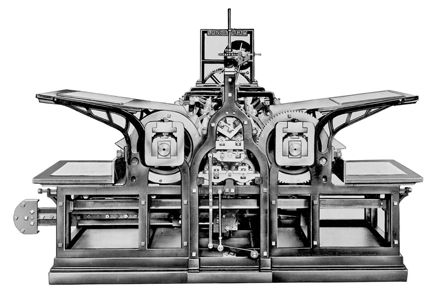

While the Stanhope press is identified with the introduction of iron in press manufacture, it was based on the same hand operated screw technique invented by Gutenberg in 1440. Alongside iron, the key advancements in the industrialization of print were the cylinder and steam power. Patent and business records of the period identify the first press that had all these features with Friedrich Koenig.

Koenig was born on April 17, 1774 in the town of Eisleben, Saxony. As manufacturing society was emerging, the bookseller and printer shared with others the desire to mechanize the hand press. Koenig’s first invention arrived 1803 with what was known as the Suhl press, a steam powered system that had inking rollers. Due to the difficult economic conditions of early 1800s Germany—including lack of a functioning patent system—Koenig moved to London in 1806 to pursue his ambition as an inventor.

The Fleet Street printer Thomas Bensley, along with several other English investors, were convinced of Koenig’s genius and agreed to finance his press experiments. Fellow countryman and engineer Andreas Bauer (1783–1860), joined Koenig in London and they developed two new platen designs for which they achieved patents in 1810 and 1811.

The significant breakthrough came in 1812 with the invention of a steam-driven cylinder machine. Koenig wrote about it in The Times, “Impressions produced by means of cylinders, which had likewise been already attempted by others, without the desired effect, were again tried by me upon a new plan, namely, to place the sheet round the cylinder, thereby making it, as it were, part of the periphery.”

Koenig’s solution of the problem of effectively transferring a letterpress image to paper by means of a cylinder won him recognition. His method was first used in book production and later, after John Walter II of The Times joined the partnership with Bensley, in newspaper printing. At Walter’s request, Koenig and Bauer built a double machine—being fed with sheets of paper from both ends—and obtained a patent for this device on June 23, 1813. The first issue of The Times printed with this technology was on November 29, 1814.

Walter wrote in The Times on that day, “Our journal of this day presents to the public the practical result of the greatest improvement connected with printing, since the discovery of the art itself. … A system of machinery almost organic has been devised and arranged, which, while it relieves all human frame of its most laborious efforts in printing, far exceeds all human powers in rapidity and dispatch. … Of the person who made this discovery, we have little to add. … It must suffice to say farther, that he is a Saxon by birth; that his name is Koenig; and that the invention has been executed under the direction of his friend and countryman Bauer.”

In 1816, Koenig and Bauer developed a perfecting cylinder press that was installed at Bensley’s business. This system produced up to 1,000 perfected sheets an hour. By this time, the two inventors wanted to sell their systems to the trade but Bensley refused. Koenig and Bauer decided to return to Germany to manufacture presses under their own name and, on August 9, 1817, they founded their own firm in Oberzell near Würzburg, Germany.

Their company continued to play a significant role in the industrial evolution of printing machines as steam power gave way to electric motors and also after the death of Friedrich Koenig on January 17, 1833. The company of Koenig and Bauer exists to this day (as KBA) at the same location and is the oldest printing press manufacturer in the world.

While European (both English and German) inventors dominated the early period of powered cylinder presses, the center of gravity for printing technology shifted to America around mid-century and especially following the Civil War. The significant expansion of the US market and the emergence of conditions for experiment and manufacturing made it the ideal environment for further strides in printing press development. This will be the subject of the next two parts of this review.