As mentioned previously, a significant driving force behind the industrial transformation of printing was the expansion of newspaper publishing. In 1840 there were 1,300 newspapers in America; by 1850 this number had doubled and most big cities had multiple daily papers. New York had fifteen dailies, Boston twelve, and Philadelphia and New Orleans each had ten.

By 1860, the telegraph and transatlantic cable increased the speed of news delivery and the largest circulation paper in the world—New York Herald—was distributing 77,000 copies daily. When the Civil War began on April 12, 1861, the New York Herald’s circulation shot up to 107,000 and did not fall below 100,000 until after the war. By this time, there were about 3,700 newspapers in the US and 387 of them were daily papers.

This was the beginning of the era of enormous publishing empires and major investments were being made in press technology development. The limitations of previous generation powered rotary presses had to be overcome in order to satisfy America’s population growth and the exploding demand for news in printed form.

In 1835, the English inventor and pioneer of the modern postal system, Sir Rowland Hill, suggested printing on both sides of a roll of paper. However, as has been the case with many previous printing press ideas, it is one thing to make a suggestion and quite another to execute it practically.

There were several important technical issues involved in the first successful rotary web printing press. The most important of these was the rapid cutting off and delivery of the paper either before or after it was printed.

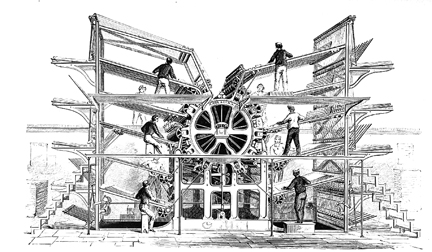

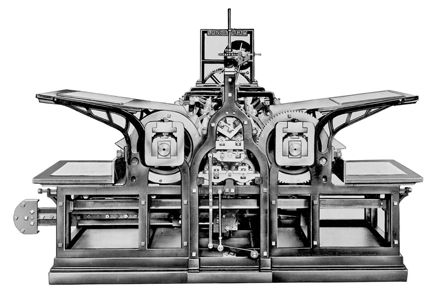

The solution to the problem of web cutoff is widely recognized as being made by the inventor William Bullock in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania beginning around 1861. In the patent granted to Bullock on April 14, 1863, the inventor describes the significance of his achievement: “My improved machine for printing from moving type or stereotype-plates belongs to that class of power printing-presses in which the paper is furnished to the machine in a continuous web or roll, and by which the sheets are severed from the web, printed on both sides, and delivered from the machines thus ‘perfected.’ … In my machine, however, there is but one delivery apparatus, which is simple in construction and works as rapidly as the machine can be driven and the sheets printed, so that by my invention the great obstacle to the rapid operation of the printing press is successfully overcome.”

The prototype of Bullock’s breakthrough system was installed at the Cincinnati Times in 1863 and the Philadelphia Inquirer acquired the first fully functioning model in 1865. The essential components of Bullock’s rotary web cutoff technology remain in use to this day in web presses all over the world.

William Bullock’s biography is one of a harsh life and, ultimately, tragic death. Born in 1813 in Greenville, NY and orphaned shortly thereafter, Bullock was apprenticed at the age of eight to a foundry man and machinist by his brother. By the age of 21, William had his own shop and was working diligently as an inventor.

He moved to Savannah, GA in the late 1830s after inventing a shingle-cutting machine and where he also built hay and cotton presses. He returned to New York and made artificial legs and invented a grain drill, seed planter and a lath-cutting machine. In 1849 he won second prize by the Franklin Institute for his grain drill.

Bullock’s interest in printing presses began in the 1850s. He was editor of The American Eagle in Catskill, NY in 1853 and then moved to New York City to work as a mechanical engineer. He ended up building a high-speed press for the nationally circulated Leslie’s Weekly in 1860.

William Bullock moved to Pittsburgh in 1861 and it seems he had aspirations of becoming a patent attorney having considerable experience with patent filings. It was around this time that he changed his listing in a Pittsburgh business directory to “manufacturer of printing presses.”

The original Bullock press design cut the paper off before printing on it. Later models of his machine cut the web after it had been printed upon, just as it is done today in the majority of web fed presses. Later, a folder invented by Walter Scott and multiple webs were added to the system further improving press productivity.

William Bullock did not live to see these additions to his invention. On April 12, 1867, he died from injuries sustained when his leg became entangled in the drive mechanism of a press he was installing at the Philadelphia Public Ledger. Bullock is buried in Union Dale Cemetery on Pittsburgh’s North Side. He was belatedly recognized in 1964 as one of the city’s geniuses with a bronze memorial marker that reads: “His invention of the rotary web press (1863) made the modern newspaper possible.”

The industrial development of printing—much like our present digital, Internet and social media era—transformed the landscape of information and news publishing and distribution. Those who studied and understood the form and content of the successive waves of technology revolution were able to take advantage of the opportunities that presented themselves. Individuals like Friedrich Koenig, Richard March Hoe and William Bullock exemplified the best of their respective generations as printing passed through a transformative period during the nineteenth century.