My mother, Dr. Corrine Louise Russell Donley, would have been 88 years-old last Tuesday. Her birthday fell exactly sixteen weeks after I learned that she had died peacefully in her sleep sometime in the early morning hours of December 19, 2023.

I consider myself extremely fortunate to have seen her for the last time one month earlier on my own birthday. It was on a Saturday, and I planned a trip from Southfield, Michigan to her retirement community in Stow, Ohio and spent the day with her.

It was a memorable visit because we went to the Cleveland Museum of Art to see an impressionist exhibit that was especially important to her. We also went out for dinner and had a long talk. That experience on my 64th birthday is special to me because it is a memory that highlighted my mother’s most enduring qualities and, looking back on it now, reminded me of who she really was.

In thinking about my mother’s life, I can tell you she was a beautiful blond with piercing blue eyes and that she was an exceptionally talented and gifted musician and pianist. I can also tell you she was a dedicated homemaker and loving mother who, along with her husband of 29 years and my father, Loren D. Donley, raised me and my three siblings, Mark, Dana and Cheryl.

I will tell you my mother was an organizer of people and things, and she maintained an At-A-Glance day planner her entire life. She was meticulous with money, and, because of that, we were able to take long trips during the summers while my parents were off from school and their teaching jobs.

My mother loved to knit and, when we were kids growing up, it was not uncommon for her to knit clothes for us or to see her sitting at the sewing machine making things for us to wear, even though, when we were old enough to know the difference, we didn’t want to wear them in the first place.

Finally, I will share that she was an outstanding public school elementary and special education teacher who went on in academia to receive her doctorate and excel both nationally and internationally in the specialized field of applied behavior analysis.

All these things are true. However, it is also true that these attributes and accomplishments, as important as they are, only partially tell the story of who my mother was and why she came to have such drive and seemingly endless compassion and empathy for others.

Corrine Louise Russell was born in East Liverpool, Ohio on April 9, 1936, to Mildred Louise Shenton Russell and John Louis Russell. My grandparents were very young when they started their family, and my mother was their first child. She was born during the Great Depression and the conditions of life in East Liverpool—a small industrial town on the Ohio River across from the northern-most point of the West Virginia panhandle—were harsh.

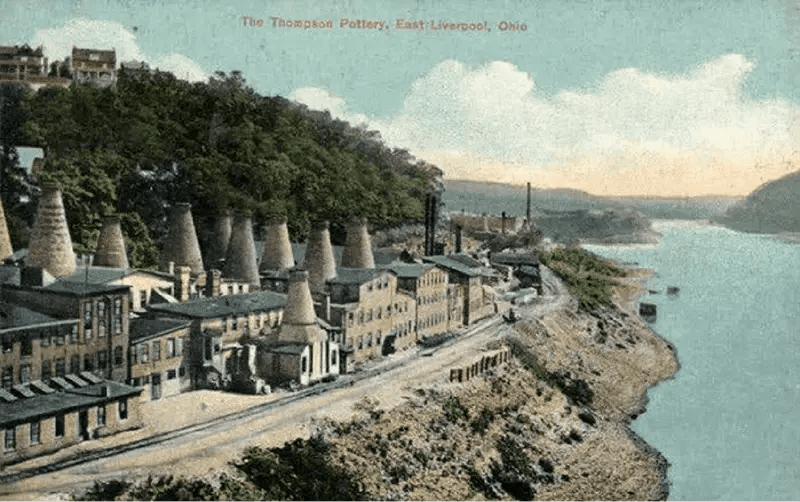

East Liverpool was founded in the late 18th century by Irish settlers who named it after Liverpool, England. During its glory days in the late 19th century, East Liverpool was known as “Crockery City,” because more than 100 pottery factories were in and around the town, some of which were across the river in West Virginia and others further east in Pennsylvania.

The pottery industry settled into this region of The Upper Ohio Valley because there was a plentiful supply of clay in the area that was suitable for making dishes. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the pottery businesses became so successful that people of Irish, English, German, Italian, Greek, Jewish and African-American descent came to East Liverpool for work.

For example, my great-great grandfather, Samuel Shenton, was a potter who had emigrated from England to East Liverpool in 1869. Samuel began working as a dish-maker in his native town of Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire at age 9 and, along with many of his fellow workingmen, decided to make the trip across the Atlantic to seek a better life in America. When he arrived at age twenty-nine, Samuel was already an expert dish-maker and one of the first white-dish makers of East Liverpool.

Samuel became a Master Workman and member of the Knights of Labor. He was a highly respected member of the East Liverpool potter’s community because of his activity during the strikes and lockouts of 1884. This was before the establishment of the 8-hour workday and the conflict between the potters and the employers was centered on how machines were being used to eliminate jobs. Samuel was blacklisted by the employers in East Liverpool and forced to relocate for 18 years in another town in Ohio where they did not know who he was.

All four of Samuel’s sons became potters and dish-makers, including Byron Shenton, my mother’s grandfather, who lived in Kittanning, Pennsylvania, a pottery town along the Allegheny River where my grandmother Mildred Louise was born.

In 1942, after the US entered World War II, Mildred Louise and John Russell had difficulty finding work and they decided to pack up my mother and her sister, my Aunt Joan, and move the family to Cleveland. It was there that John took a job as an electrician in a military aircraft factory and Mildred became a taxi driver.

When the war ended, the Russell family moved back to East Liverpool. However, the pottery industry was by this time decimated by the Great Depression and overseas dishware competition. The local economy never returned to that of its prewar years. Due in part to these circumstances, Mildred Louis and John divorced and there were times when my mother was sent to live with grandparents or aunts and uncles and did not see her parents for long stretches of time.

The hardship associated with the economic decline of East Liverpool impacted many families during those years. My mother told me that President Roosevelt’s New Deal programs—which brought jobs, Social Security and other government aid to the area—was so popular among the people of East Liverpool that a classmate of hers was given the name “Welcome FDR,” when he was born. They called him Welkie.

As a child, my mother was precocious, and she developed a remarkable determination to overcome the poverty she was growing up in. She described to me some of the homes of East Liverpool residents which were essentially shacks made with random boards covered with tin can shingles and with dirt floors. She spoke compassionately about how some local people suffered from illiteracy and a lack of health care and dental care and from tobacco and alcohol abuse.

She told me about the house on Morton Street that the Russell family had moved into when she was 12. The home was nearly at the top of the hillside on which East Liverpool stood and you had to drive up extremely steep streets to get to it. The home initially had an outhouse and, when a bathroom was finally added, it was a box on stilts that was attached to the outside of the upper level. When entering the bathroom, she told me, she could see the ground below through a gap in the floor between the two structures.

Meanwhile, life in East Liverpool was fraught with many difficulties and obstacles for a young girl. She told me many times that, when speaking to others about her plans to do great things with her life, she was told more than once, “You won’t amount to anything. You’ll be barefoot and pregnant by the time you’re 16.” She also told me about abuses she suffered as a girl which were unfortunately common and the result of the poverty and backwardness that existed in the community.

While her experience was by no means entirely unique, the memories of what life was like in her childhood stayed with my mother. However, she never let those things keep her from educating herself and pursuing her goals. She did not allow the negative aspects of her upbringing to become a justification for what she could not do or to live a life of bitterness about how she was mistreated or how she never received the support she deserved as a child growing up.

Instead, these challenges and disappointments became her springboard; they became a source of energy and determination to set high expectations and strive to overcome all obstacles to meet them. She also used them to dedicate herself to helping others overcome their disadvantages and disabilities.

My mother was part of a generation of young women who, in the post-war years, benefited from access to public education and the expanding role of women in the workplace and society. Meanwhile, as part of that generation, my mother had a deep-going social awareness and concern for those less fortunate than her. She wanted to make a difference in the lives of others and this led her into special education, where she became a pioneer in the classroom and one of the first in the field to use music therapy for the handicapped and people with intellectual disabilities.

And this is what brings me back to our trip to the Cleveland Museum of Art on my birthday last November. One of the most important experiences I had growing up as the son of Corrine Louise Russell Donley was that she taught me and helped me learn about fine art. I recall when going on trips with the family during the summer that we would make stops to visit art galleries and exhibits.

At the time, like many children, I did not understand what she was doing. I would complain about having to go to the galleries and ask, “Mom, do I have to go with you to the museum?,” and she would always say, “Yes, you do.” She never let up on this.

By the time I was in high school, I knew about the paintings of modern artists like as Jackson Pollack, Paul Klee and Pablo Picasso. I was also familiar with the works of American painters like Andrew Wyeth, Winslow Homer, Grant Wood and Norman Rockwell. Today, my wife Denise and I have my parents’ print of Winslow Homer’s “The Country School” hanging on the wall in our living room. That painting was positioned for decades over the piano in the living room of the Donley household in Point Pleasant, New Jersey.

Anyway, I developed an appreciation for the periods and methods of the artists and, by the time I was ready to leave home for college, I had formulated my own interest in fine art painting and, it turns out, this was a factor in my decision to pursue graphic arts as a career choice. I have my mother to thank for this.

The important exhibit she wanted to see in Cleveland was called “Degas and the Laundress: Women, Work and Impressionism.” It was the first exhibition to feature the impressionist Degas’ paintings and sketches of Parisian laundresses which he had made over his long career beginning in 1850. The exhibition also included paintings of laundresses by other artists, such as Picasso, Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec and Daumier, who were inspired by Degas and his focus on these Parisian women.

Degas, who is most well-known for paintings of ballet dancers, horse races and upper middle class life in Paris, was drawn to the laundresses. A perpetual and visible presence in the city, the women could be seen at all times of the day washing clothes in the river, carrying heavy baskets of laundry or ironing in the many shops that were open to the street.

The laundresses were among the most marginalized, poorly paid and exploited people in Paris. Their job was arduous and dangerous, as they carried out strenuous and repetitive work while being exposed to chemicals and diseases. A remarkable aspect of Degas’ paintings of the laundresses of Paris is that he concentrated on images of these women while they were at work.

The Cleveland Museum of Art was not especially busy on my birthday, and we were able to find the special Degas exhibit easily. When my mother and I came upon the featured and most famous painting in Degas’ laundress series, we stopped there for a long time to observe it. The painting, entitled Woman Ironing, was painted by Degas in 1869 and the subject is based on a model named Emma Dobigny whom the artist had befriended.

The painting is remarkable because it has additional lines drawn of Dobigny’s arms as if they are in motion while she irons a gray muslin dress on the table. The expression on her face is one of exhaustion but also, as she stares straight at the artist, she seems to be saying, “Yes, this is difficult work, but I am strong, and I will not stop until it is complete.”

As I think about what we saw in that painting, I am now realizing what was going through my mother’s mind in that moment. Corrine Louise Russell Donley was nearing the end of her life. She had suffered several serious heath events that forced her to use a walker, and, in this instance, I was pushing her through the museum in a wheelchair. What my mother saw, as we looked at the Paris laundress, was someone with whom she identified.

Although she did not and could not have known on that day she would be gone in one month, my mother was determined, and I know she was thinking about all the things she had yet to do and how much more she had to give to the world. She was thinking, “I have come through many challenges, had a long life and accomplished important things. However, my work is not done yet.”