The American Association of Publishers recently reported that year-over-year e-book sales had fallen by nearly 5% through mid-2013. The “flattening” of e-book sales has been underway for several years and the latest figures come as no surprise. The exponential growth rates of the e-book market that began in 2008—peaking at 254% in the first quarter of 2010—could not be sustained indefinitely. As Harper-Collins CEO Brian Murray noted last November to Publishers Weekly, “Nothing grows by triple digits for too long.”

There are dynamic and complex reasons for the e-book market slowdown: the popularity of individual titles, sales of dedicated e-reader devices vs. tablets, recognition by readers and publishers of titles that fit one format vs. another, etc. Meanwhile, one byproduct of these changes is that the decline in printed book sales—particularly hard cover books—has also begun to slow. It seems that some kind of equilibrium is being achieved between printed books and their digital cousins. Industry experts say that this is a repetition of the pattern of development that occurred when paperbacks (1930s) and audio books (1970s) first came into use.

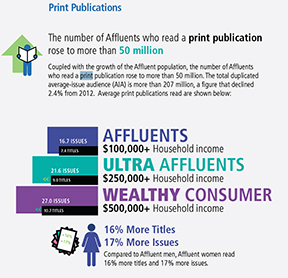

The following is a summary of the recent AAP book sales figures by format:

Format Jan-Jun 2013 Jan-Jun 2012 Change

Hardcover $978.1 million $1,063.8 million -8.0%

Paperback $953.5 million $1,023.3 million -6.8%

E-book $766.8 million $805.3 million -4.8%

Total $2,698.4 million $2,892.4 million -6.7%

One important aspect to note is that within an overall environment of declining book sales, e-book sales as a percent of the total is continuing to grow (from 27.8% in 2012 to 28.4% in 2013).

The inflection point in the e-book market is an appropriate moment to take note of the publication earlier this year of the volume The Book: A Global History by Oxford University Press. Edited by Michael F. Suarez and H.R. Woudhuysen, The Book contains 54 essays in two sections: Thematic Studies (21 essays) that deal with the origins of written communications, the ancient history of books and the technologies of book production and Regional and National Histories of the Book (33 essays) that cover book history in many countries in Europe, Asia, Australia and the Americas.

The new volume is a concise edition of the highly acclaimed Oxford Companion to the Book published in 2010. That work by the same editors is 1,327 pages, comes in two vivid burgundy bound volumes with gold lettering, costs $325 and is clearly library reference material.

The new volume is a concise edition of the highly acclaimed Oxford Companion to the Book published in 2010. That work by the same editors is 1,327 pages, comes in two vivid burgundy bound volumes with gold lettering, costs $325 and is clearly library reference material.

As Suarez and Woudhuysen state in the introduction to the new smaller volume, “Encouraged by the commercial and critical fortunes of The Oxford Companion to the Book (2010), its General Editors were nonetheless chastened by the fact that its costliness prevented many from purchasing the two-volume work of 1.1 million words. … It is our hope that the publication of this volume will make a valuable collection of bibliographical and book-historical scholarship—ambitious in its scope and innovative in its reach—accessible to a broad audience of general readers and advanced specialists alike.”

One can tell from these two sentences that this is not a book to be read for entertainment. In any case, The Book: A Global History—in spite of its pedanticism and academic erudition—is an important resource. The research and scholarship enable those in modern day print communications to gain a deeper understanding of their profession and its social, technical and economic origins and development over many centuries.

For example, in a significant point in the introduction, the editors describe the term “book” as a synecdoche, i.e. a figure of speech that represents all other textual communications forms. They write, “Naturally, the use of the term ‘book’ in our title in no way excludes newspapers, prints, sheet music, maps or manuscripts … in every European language the word for ‘book’ is traceable to the word for ‘bark,’ we might profitably think of ‘book’ as originally signifying the surface on which any text is written and, hence, as fitting shorthand for all recorded texts.”

It is of course not possible to summarize the entirety of the new volume here, so below are a few highlights followed by some concluding thoughts:

- Writing Systems

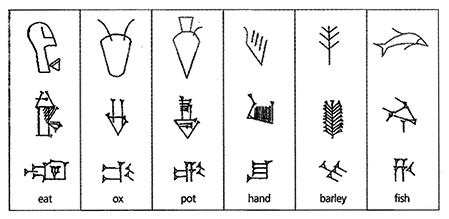

The very first essay by Andrew Robinson is about the origin of human writing systems. It should come as no surprise that the birth of writing is thought to have taken place in what is now known as the “cradle of civilization” in Mesopotamia sometime in the late 4th millennium BC. The impulse for the first writing system was the need for record keeping associated with trade. As Andrews writes, “the complexity of trade and administration had reached a point where it outstripped the power of memory among the governing elite. To record transactions in an indisputable, permanent form became essential.” One theory holds that the system began with the exchange of clay tokens and that this was later substituted with two-dimensional symbols written in clay. Of course, another origin of writing is the Ice Age symbols found in caves in southern France that date back 20,000 years. These images, however, are considered “proto-writing” because they do not conform to the scientific definition of writing provided by the noted Sinologist John DeFrancis as a “system of graphic symbols that can be used to convey any and all thought.”

- The Book as Symbol

In essay number 7, Brian Cummings treats the book as an object within different historical contexts. He writes, “A book is a physical object, yet it also signifies something abstract, the words and the meanings collected within it. Thus, a book is both less and more than its contents alone.” During ancient times, books were considered sacred and access was restricted to a priestly class. Writing was itself considered a spiritual power and consumption of the written words also a mystical act. Later, Plato posited that writing was inferior and untrustworthy in comparison to the knowledge within the mind. In biblical times, “the scrolls” (Torah), “the tablets” (Ten Commandments) and “the scriptures” (The Bible) emerged as those writings that embodied divine power, law and ordinance. Cummings writes, “The incorporation of the holy book into ritual—the raising of the book, or carrying of it in procession, or kissing of the book or kneeling before it—is only the most obvious example of this.” These practices exist today in the courtroom or inaugural “swearing-in” and “taking the oath” of witnesses and officials who place their hand upon the Bible. Another more modern and historically significant treatment of books was the infamous Nazi burning of “degenerate” books in Berlin’s Opernplatz in 1933.

- The Electronic Book

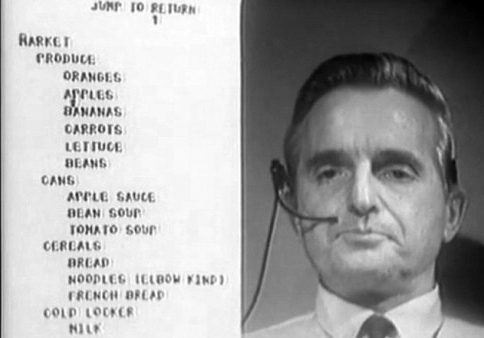

The essay by Eileen Gardiner and Ronald G. Musto on the e-book was revised and expanded from the Oxford Companion to the Book of 2010 and this fact expresses the rapid development of the new form. Of particular note is the essay’s summary of the background to present-day e-books. In 1945, Vannevar Bush provided the earliest documented vision for proto electronic books in what he called the Memex. This hypothetical system would store the entire contents of scientific literature and had pages, page-turners, annotation capability, internal and external links, storage, retrieval and transmission of documents. But, while Bush conceived of the Memex on microfilm, the first truly electronic book concept came in 1965 with the “hyperlinking,” “hypertext” and “hypermedia” vision of Ted Nelson. Nelson’s idea was first demonstrated—now famously referred to as “The Mother of All Demos”— by Douglas Engelbart. The system was called NLS (for oNLine System) and was developed by the Stanford Research Institute. Engelbart demonstrated in combination for the first time anywhere on December 9, 1968 the following: email, teleconferencing, video-conferencing and the mouse. The future of hypertext from this point forward merges directly with the emergence of the personal computer and later the World Wide Web, i.e. Apple HyperCard by Bill Atkinson in 1987, the emergence of CD-ROM books in 1992, online and searchable texts accessible with the Mosaic/Netscape web browser in 1993.

As mentioned earlier, The Book: A Global History is an important resource for bibliophiles and anyone seeking thorough knowledge of the history of print communications. Going through the volume, readers gain a better understanding world history. It seems that books, both their antecedents and descendants, are intermingled with the history of all civilization from the end of human pre-history to the present.

With the development and adoption of e-books—combined with wireless and mobile communications—it is possible to envision a future where print-on-paper books are recognized as relics of a distant past. But such an eventuality would also require a development well beyond the present e-book reader and mobile media experience along with solving many other complex problems. While great strides have been made, we are still at the very beginning of the transition from the completely analog world of books to the completely digital world of instantaneous and infinite access to all information, knowledge and culture.