Linn Boyd Benton is not a widely known figure in the history of printing. This is an odd fact given that he is responsible for one of the most important technical achievements of the late nineteenth century: the invention of the pantographic engraver of type punches. Without Benton’s contribution, the completion of the industrialization of the printing process—and the success of Mergenthaler’s Linotype casting machine—would not have been possible.

Linn Boyd Benton was born on May 13, 1844 in Little Falls, New York, a town about 75 miles east of Syracuse. His father, Charles Swan Benton, was a lawyer and the founder-editor of the Mohawk Courier & Little Falls Gazette. In 1840, the elder Benton was elected as US Representative of the 17th District of New York State.

It has been said that Linn Boyd was forced to rely upon himself at an early age because his mother, Emeline Fuller of Little Falls, died when he was just three years old. That his father moved the family frequently also contributed to Linn Boyd’s character development.

After Charles remarried, he relocated the family to Milwaukee, Wisconsin where he became part owner and editor of the Milwaukee Daily News. At age eleven, Linn Boyd had his first experience with typography in the composing room of his father’s newspaper.

Boyd—as he was called—attended Galesville College, in Galesville, Wisconsin and studied advanced subjects for two years with a private tutor in La Crosse, Wisconsin. He developed his mechanical aptitude while working summer jobs as a tombstone cutter and as a watch repairman for a jeweler in La Crosse.

At 22 years old, Boyd was hired by a friend of his father’s as a bookkeeper for a Milwaukee type foundry. When the company went bankrupt during the financial panic of 1873, Boyd bought the Northwestern Type Foundry along with a partner and ran the manufacturing operations of the business. This was the beginning of Linn Boyd Benton’s long career in typography.

After several name and partnership changes, Boyd remained operations director of Benton, Waldo & Company and, by the early 1880s, the firm was manufacturing and selling metal type in the highly competitive industry. It was during this time that Benton began developing his skills as an inventor and typographic innovator.

Self-spacing type

By the 1880s, the problem of standardized type size measurement had become the scourge of the printing industry. Most printing establishments were forced to maintain relationships with a single type foundry due to the fact that type sizes, widths, base alignment and even metal alloy composition were not common.

With the industrial development of printing machinery long established—the launching of daily newspapers and installation of large steam-powered rotary web presses taking place everywhere—the lack of advanced methods of type specification, manufacture and composition were holding the industry back.

Since the early 1700s efforts had been mounted in Europe and America to come up with a standard for measuring type. The “pica and point” system finally emerged after a long conflict over proprietary interests. On September 17, 1886 the American System of Interchangeable Type Bodies was formally adopted at a meeting of the United States Type Founder’s Association in Niagara, New York.

Within this environment, Linn Boyd Benton began working on methods that would change the way type was specified and handled. The problem facing compositors was that justifying a line of type required the manual arrangement of individual characters and spacers with a “trial and error” working method. According to Benton and others, this antiquated process unnecessarily lengthened composition time and there had to be a means of automating it.

The measuring system of “12 points to a pica and 6 picas to an inch” that we use today was initially developed as a vertical system of type height. Benton’s innovation was that the width should also be measured such that the typography followed “the point system both ways.” In 1883, Benton received US Patent 290,201 for Self Spacing Type that, according to the promotional literature, could “increase composition speeds by 25%.”

The Benton, Waldo & Company’s Self Spacing Type styles were designed primarily for the newspaper industry where compositor speed was the most important issue. For some typographers, the horizontal distortion of characters and spaces required to make Benton’s system work meant that the visual appearance of the type was unacceptable; they argued it was hard to read.

Nonetheless, Benton’s work on self-spacing type was a breakthrough and the production and marketing of its typefaces brought him straight into a much more historically significant technological advancement for the industry.

Benton’s pantographic punch cutting machine

To grasp the significance of Benton’s invention of the pantographic engraver, it is important to understand the components and process of metal typesetting. Gutenberg’s accomplishment was the invention of the hand-held mold for typecasting. It created the mass production of individual metal characters that could be assembled into lines and pages of type, effectively displacing the handwriting by scribes.

There are two preliminary steps required in the production of the type mold into which the molten metal is poured: the punch and the matrix. The punch is a steel relief form of the letter that is driven by a hammer into a piece of copper that creates the cavity of the matrix. The matrix is then placed into the mold assembly where hot metal is poured forming the finished piece of type that will be inked and printed upon.

Prior to Benton, punch cutting was a manual process that required a highly skilled craftsman to design and engrave the characters into a tapered piece of steel that was two to three inches long. Every character of every size had to be punch cut; these were the “masters” of the font from which many matrices could be produced. If a punch was damaged or broken, it would have to be remade by hand and it was likely that there would be slight differences from the one to the other.

Punch cutting was clearly the most difficult job in the production of type. It was not uncommon for a skilled punch cutter to take an entire day to make one punch; each punch required the continuous use of a magnifying glass, significant manual dexterity and an esthetic sensibility.

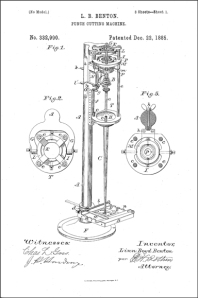

Benton’s Self Spacing Type required the cutting of more than 3,000 punches and skilled punch cutters were in short supply. In an effort to solve this problem, Linn Boyd Benton employed the pantograph—a mechanical device that uses parallelograms to trace an image on one surface and reproduce that image precisely on another surface—in the type production process.

Although Benton was not the first person to employ the pantographic principle in type making, he was the first to obtain a patent for the machine that would ultimately be used for cutting steel punches. The device went through several iterations and it has been established that the first machine did not cut punches but actually was used to engrave the metal letters themselves. However, Benton’s third pantographic engraver that was granted US Patent 332,990 was designed specifically for punch cutting.

Coincidentally, while Benton was solving problems with self-spacing type manufacturing, Ottmar Mergenthaler was developing a solution for the mechanical composition of type, one complete line at a time. With the investment of powerful newspaper publishing interests behind him, Mergenthaler invented the Linotype machine in 1886 and by 1888 there were hundreds of these machines on order.

Mergenthaler’s Linotype breakthrough begged for a method of mass matrix production on a scale that had never before existed. As explained by Benton’s publicist Henry Lewis Bullen, “Here was a machine; but no adequate means of supplying it with matrices had been devised. The rapid production of matrices required the rapid production of punches. … In 1890 the Linotype company had six or seven punch cutters in its employ and these could do no more than keep up supply of matrices for about two hundred machines. Not in all the world could enough steel punch cutters be found to furnish an adequate supply of matrices, without which the machines were as useless and unsalable as a gun where powder is unprocurable.”

By chance, Benton’s partner R.V. Waldo was on a self-spacing type sales visit at New York Tribune where Mergenthaler’s machine was pioneered. Once the topic of Benton’s pantograph came up between Waldo and Mergenthaler’s representatives it was just a matter of time before the Linotype matrix production dilemma would be solved. On February 13, 1889, the first Benton punch-cutting machine was leased to the Mergenthaler Printing Company.

Thus, the combined accomplishments of Benton and Mergenthaler terminated the era of hand crafted type production and enabled this most important aspect of print technology to completely enter the industrial age.

Later years

Linn Boyd Benton would go on to make many other technical contributions to the printing and typographic industries: combination fractions (1895), a type dressing machine (1901), an automatic type-caster (1907), and a lining device for engraving matrices of shaded letters (1913). Benton also played an important role with Theodore Lowe De Vinne in the design of the Century Roman typeface, an innovation in type design at the beginning of the twentieth century.

In 1892, Benton, Waldo & Company merged with 23 other type houses and formed the American Type Founders Company with headquarters in Elizabeth, NJ. At the time it represented 85% of all type manufactured in the US and would dominate the industry into the 1940s.

Morris Fuller Benton, Linn Boyd’s only son who was born in Milwaukee in 1872, would join the ATF organization at age 24 after graduating from Cornell with an engineering degree. Morris would go on to be a major contributor to the type business and a force of his own in printing history completing 221 typeface designs—including Cheltenham, Hobo, Broadway and Franklin Gothic—during his career.

Linn Boyd Benton retired from ATF on July 1, 1932 and died two weeks later on July 15, 1932. Along with recognition of his many accomplishments, the company’s board of directors described Benton in a statement the following October: “As a Man Mr. Benton endeared himself to us by his modesty, his delightful humor and his probity in all matters, intellectual and material.”

This complete account of Lynn Boyd Benton’s somewhat important contributions to the printing history highlights gifts that had been previously hidden. Thank you.