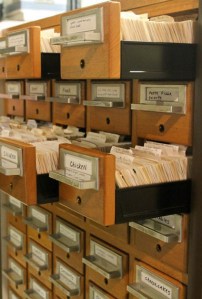

One year ago this month, the final order of library catalog cards was printed by the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) in Dublin, Ohio. On October 2, 2015, The Columbus Dispatch wrote, “Shortly before 3 p.m. Thursday, an era ended. About a dozen people gathered in a basement workroom to watch as a machine printed the final sheets of library catalog cards to be made …”

One year ago this month, the final order of library catalog cards was printed by the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) in Dublin, Ohio. On October 2, 2015, The Columbus Dispatch wrote, “Shortly before 3 p.m. Thursday, an era ended. About a dozen people gathered in a basement workroom to watch as a machine printed the final sheets of library catalog cards to be made …”

The fate of the printed library card, an indispensable indexing tool for more than a century, was inevitable in the age of electronic information and the Internet. It is safe to say that nearly all print with purely informational content—as opposed to items fulfilling a promotional or a packaging function—is surely to be replaced by online alternatives.

Founded in 1967, the OCLC is a global cooperative with 16,000 member libraries. Although it no longer prints library cards, the OCLC continues to fulfill its mission by providing shared library resources such as catalog metadata and WorldCat.org, an international online database of library collections.

Speaking about the end of the card catalog era, Skip Prichard the CEO of the OCLC said, “The vast majority of libraries discontinued their use of the printed library catalog card many years ago. … But it is worth noting that these cards served libraries and their patrons well for generations, and they provided an important step in the continuing evolution of libraries and information science.”

The 3 x 5 card

Printed library catalog card

Printed library catalog cardThe library catalog card is one form of the popular 3 x 5 index card that served as a filing system for a multitude of purposes for over two hundred years. While many of us have been around long enough to have used or maybe even still use them—for addresses and phone numbers, recipes, flash cards or research paper outlines—we may not be aware of the relationship that index cards have to modern information science.

The original purpose of the index card and its subsequent development represented the early stages of information theory and practice. Additionally, as becomes clear below, without the index card as the first functional system for organizing complex categories, subcategories and cross-references, studies in the natural sciences would have never gotten off the ground.

The index card became the indispensable tool for both organizing and comprehending the expansion of human knowledge at every level. Along with several important intermediary steps, the ideas that began with index cards eventually led to relational databases, document management systems, hyperlinks and the World Wide Web.

Carl Linnaeus and natural science

Carl Linnaeus

Carl LinnaeusThe Swedish naturalist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) is recognized as the creator of the index card. Linnaeus used the cards to develop his system of organizing and naming the species of all living things. Linnaean taxonomy is based on a hierarchy (kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species) and binomial species naming (homo erectus, tyrannosaurus rex, etc.). He published the first edition of his universal conventions in a small pamphlet called “The System of Nature” in 1735.

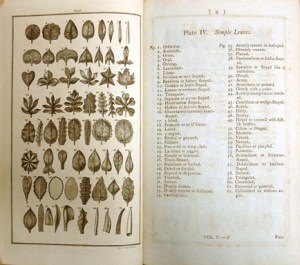

Beginning in his early twenties, Linnaeus was interested in producing a series of books on all known species of plants and animals. At that time, there were so many new species being discovered that Linnaeus knew as soon as a book was printed, a large amount of new information would already be available. He wanted to quickly and accurately revise his publications to take into account the new findings in subsequent editions.

As time went on, Linnaeus developed different functional methods of sorting through and organizing enormous amounts of information connected with his growing collection of plant, animal and shell specimens (eventually it rose to 40,000 samples). His biggest problem was creating a process that was both structured enough to facilitate retrieval of previously collected information and flexible enough to allow rearrangement and addition of new information.

Pages from an early edition of Linnaeus’ “The System of Nature”

Pages from an early edition of Linnaeus’ “The System of Nature”Working with paper notations in the eighteenth century, he needed a system that would allow the flow of names, references, descriptions and drawings into and out of a fixed sequence for the purposes of comparison and rearrangement. This “packing” and “unpacking” of information was a continuous process that enabled Linnaeus’ research to keep up with the changes in what was known about living species.

Linear vs non-linear methods

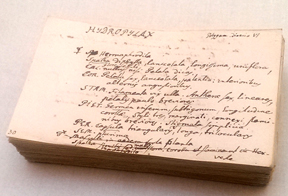

At first, Linnaeus used notebooks. This linear method—despite his best efforts to leave pages open for updates and new information—proved to be unworkable and wasteful. As estimates of how much room to allow often proved incorrect, Linnaeus was forced to squeeze new details into ever shrinking available space or he ended up with unutilized blank pages.

After thirty years of working with notebooks, Linnaeus began to experiment with a filing system of information recorded on separate sheets of paper. This was later converted to small sheets of thick paper that could be quickly handled, shuffled through and laid out on a table in two-dimensions like a deck of playing cards. This is how the index card was born.

A stack of Linnaeus’ hand written index cards

A stack of Linnaeus’ hand written index cardsLinnaeus’ index card system was able to represent the variation of living organisms by showing multiple affinities in a map-like fashion. In order to accommodate the ever-expanding knowledge of new species—today the database of taxonomy contains 8.7 million items—Linnaeus created a breakthrough method for managing complex information.

Melvil Dewey and DDC

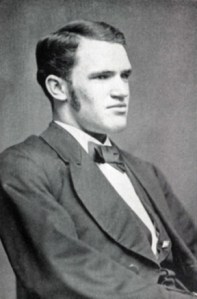

While index cards continued to be used in Europe, an important step forward in information management was made in the US by Melvil Dewey (1851-1931), the creator of the well-known Dewey Decimal System (or Dewey Decimal Classification, DDC). Used by libraries for the cataloging of books since 1876, the DDC was based on index cards and introduced the concepts of “relative location” and “relative index” to bibliography. It also enabled libraries to add books to their collection based on subject categories and an infinite number of decimal expressions known as “call numbers.”

The young Melvil Dewey

The young Melvil DeweyPrevious to the DDC, libraries attempted to assign books to a permanent physical location based on their order of acquisition. This linear approach proved unworkable, especially as library collections grew rapidly in the latter part of the nineteenth century. With industrialization, libraries were overflowing with paper: letters, reports, memos, pamphlets, operation manuals, schedules as well as books were flooding in and the methods of cataloging and storing these collections needed to find a means of keep up.

In the 1870s, while working at Amherst College Library, Melvil Dewey became involved with libraries across the country. He was a founding member of the American Library Association and became editor of the The Library Journal, a trade publication that still exists today. In 1878, Dewey published the first edition of “A Classification and Subject Index for Cataloguing and Arranging the Books and Pamphlets of a Library” that elaborated on the use of the library card catalog index.

Precursor to the information age

Title page of the first edition of Dewey’s bibliographic classification system

Title page of the first edition of Dewey’s bibliographic classification systemLike many others of his generation, Melvil Dewey was committed to scientific management, standardization and the democratic ideal. By the end of the nineteenth century the Dewey classification system and his 3 x 5 card catalog were being used in nearly every school and public library in the US. The basic concept was that any member of society could walk into a library anywhere in the country, go to the card catalog and be able to locate the information they were looking for.

In 1876 Dewey created a company called Library Bureau and began providing card catalog supplies, cabinets and equipment to libraries across the country. Following the enormous success of this business, Dewey expanded the Library Bureau’s information management services to government agencies and large corporations at the turn of the twentieth century.

In 1896, Dewey formed a partnership with Herman Hollerith and the Tabulating Machine Company (TMC) to provide the punch cards used for the electro-mechanical counting system of the US government census operations. Dewey’s relationship with Hollerith is significant as TMC would be renamed International Business Machines (IBM) in 1924 and become an important force in the information age and creator of the first relational database.

Paul Otlet and multidimensional indexing

Paul Otlet working in his office in the 1930s

Paul Otlet working in his office in the 1930sWhile Dewey’s classification system became the standard in US libraries, others were working on bibliographic cataloging ideas, especially in Europe. In 1895, the Belgians Paul Otlet (1868-1944) and Henri La Fontaine founded the International Institute of Bibliography (IIB) and began working on something they called the Universal Bibliographic Repertory (UBR), an enormous catalog based on index cards. Funded by the Belgian government, the UBR involved the collection of books, articles, photographs and other documents in order to create a one-of-a-kind international index.

As described by Otlet, the ambition of the UBR was to build “an inventory of all that has been written at all times, in all languages, and on all subjects.” Although they used the DDC as a starting point, Otlet and La Fontaine found limitations in Dewey’s classification system while working on the UBR. Some of the issues were related to Dewey’s American perspective; the DDC lacked some categories needed for information related to other regions of the world.

A section of the Universal Bibliographic Repertory

A section of the Universal Bibliographic RepertoryMore fundamentally, however, Otlet and La Fontaine made an important conceptual breakthrough over Dewey’s approach. In particular, they conceived of a complex multidimensional indexing system that would allow for more deeply defined subject categories and cross-referencing of related topics.

Their critique was based on Otlet’s pioneering idea that the content of bibliographic collections needed to be separated from their form and that a “universal” classification system needed to be created that included new media and information sources (magazines, photographs, scientific papers, audio recordings, etc.) and moved away from the exclusive focus on the location of books on library shelves.

Analog information links and search

After Otlet and La Fontaine received permission from Dewey to modify the DDC, they set about creating the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC). The UDC extended Dewey’s cataloging expressions to include symbols (equal sign, plus sign, colon, quotation marks and parenthesis) for the purpose of establishing “links” between multiple topics. This was a very significant breakthrough that reflected the enormous growth of information taking place at the end of the nineteenth century.

By 1900, the UBR had more than 3 million entries on index cards and was supported by more than 300 IIB members from dozens of countries. The project was so successful that Otlet began working on a plan to copy the UBR and distribute it to major cities around the world. However, with no effective method for reproducing the index cards, other than typing them out by hand, this project ran up against the technical limitations of the time.

Henri La Fontaine and staff members at the Mundaneum in Mons, Belgium. At its peak in 1924, the catalog contained 18 million index cards.

Henri La Fontaine and staff members at the Mundaneum in Mons, Belgium. At its peak in 1924, the catalog contained 18 million index cards.In 1910, Otlet and La Fontaine shifted their attention to the establishment of the Mundaneum in Mons, Belgium. Again with government support, the aim of this institution was to bring together all of the world’s knowledge in a single UDC index. They created the gigantic repository as a service where anyone in the world could submit an inquiry on any topic for a fee. This analog search service would provide information back to the requester in the form of index cards copied from the Mundaneum’s bibliographic catalog.

By 1924, the Mundaneum contained 18 million index cards housed in 15,000 catalog drawers. Plagued by financial difficulties and a reduction of support from the Belgian government during the Depression and lead up to World War II, Paul Otlet realized that further management of the card catalog had become impractical. He began to consider more advanced technologies—such as photomechanical recording systems and even ideas for electronic information sharing—to fulfill his vision.

Although the Mundaneum was sacked by the Nazi’s in 1940 and most of the index cards destroyed, the ideas of Paul Otlet anticipated the technologies of the information age that were put into practice after the war. The pioneering work of others—such as Emanuel Goldberg, Vannevar Bush, Douglas Englebart and Ted Nelson—would lead to the creation of the Internet, World Wide Web and search engines in the second half of the twentieth century.