On Friday, June 12, Apple released its San Francisco system font for OSX, iOS and watchOS. Largely overlooked amid the media coverage of other Apple product announcements, the introduction of San Francisco was a noteworthy technical event.

San Francisco is a neo-grotesk, sans serif and Pan European typeface with characters in Latin as well as Cyrillic and Greek scripts. It is significant because it is the first font to be designed specifically for all of Apple’s display technologies. Important variations have been introduced into San Francisco to optimize its readability on Apple desktop, notebook, TV, mobile and watch devices.

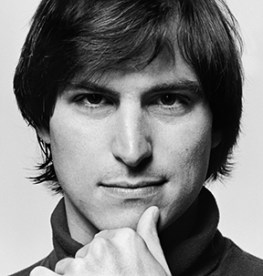

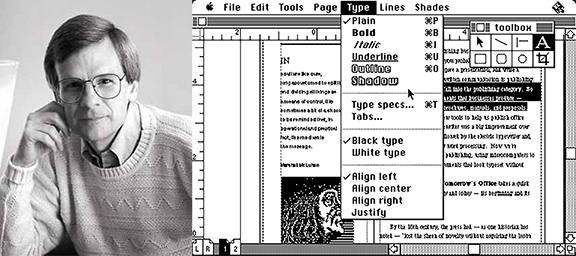

It is also the first font designed by Apple in two decades. San Francisco extends Apple’s association with typographic innovation that began in the mid-1980s with desktop publishing. From a broader historical perspective, Apple’s new font confirms of the ideas developed more than fifty years ago by renowned calligrapher and type designer Hermann Zapf. Sadly, Zapf died at the age of 96 on June 4, 2015 just one week before Apple’s San Francisco announcement.

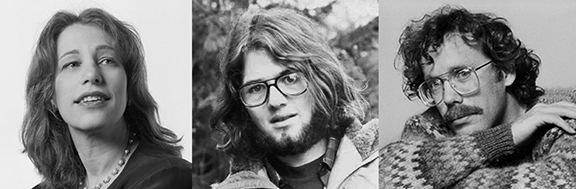

Hermann Zapf’s contributions to typography are extensive and astonishing. He designed more than 200 typefaces—the popular Palatino (1948), Optima (1952), Zapf Dingbats (1978) and Zapf Chancery (1979) among them—including fonts in Arabic, Pan-Nigerian, Sequoia and Cherokee. Meanwhile, Zapf’s exceptional calligraphic skills were such that he famously penned the Preamble of the Charter of the United Nations in four languages for the New York Pierpont Morgan Library in 1960.

While he made many extraordinary creative accomplishments—far too many to list here—Hermann Zapf’s greatest legacy is the way he thought about type and its relationship to technology as a whole. Herman Zapf was among the first and perhaps the most important typographers to theorize about the need for new forms of type driven by computer and digital technologies.

Early life

Hermann Zapf was born in Nuremburg on November 8, 1918 during the turbulent times at the end of World War I. As he wrote later in life, “On the day I was born, a workers’ and soldiers’ council took political control of the city. Munich and Berlin were rocked by revolution. The war ended, and the Republic was declared in Berlin on 9 November 1918. The next day Kaiser Wilhelm fled to Holland.”

At school, Hermann took an interest in technical subjects. He spent time in the library reading scientific journals and at home, along with his older brother, experimenting with electronics. He also tried hand lettering and created his own alphabets.

Hermann left school in 1933 with the intention of becoming an engineer. However, economic crisis and upheaval in Germany—including the temporary political detention of his father in March 1933 at the prison camp in Dachau—prevented him from pursuing his plans.

Apprentice years

Barred from attending the Ohm Technical Institute in Nuremberg for political reasons, Hermann sought an apprenticeship in lithography. He was hired in February 1934 to a four-year apprenticeship as a photo retoucher by Karl Ulrich and Company.

In 1935, after reading books by Rudolf Koch and Edward Johnson on lettering and illuminating techniques, Hermann taught himself calligraphy. When management saw the quality of Hermann’s lettering, the Ulrich firm began to assign him work outside of his retouching apprenticeship.

Hermann refused to take the test at his father’s insistence on the grounds that the training had been interrupted by many unrelated tasks. He never received his journeyman’s certificate and left Nuremburg for Frankfurt to find work.

Zapf started his career in type design at the age of 20 after he was employed at the Fürsteneck Workshop House, a printing establishment run by Paul Koch, the son of Rudolf Koch. As he later explained, “It was through the print historian Gustav Mori that I first came into contact with the D. Stempel AG type foundry and Linotype GmbH in Frankfurt. It was for them that I designed my first printed type in 1938, a fraktur type called ‘Gilgengart’.”

War years

Hermann Zapf was conscripted in 1939 and called up to serve in the German army near the town of Pirmasens on the French border. After a few weeks, he developed heart trouble and was transferred from the hard labor of shovel work to the writing room where he composed camp reports and certificates.

When World War II started, Hermann was dismissed for health reasons. In April 1942 he was called up again, this time for the artillery. Hermann was quickly reassigned to the cartographic unit where he became well-known for his exceptional map drawing skills. He was the youngest cartographer in the German army through the end of the war.

Zapf was captured after the war by the French and held in a field hospital in Tübingen. As he recounted, “I was treated very well and they even let me keep my drawing instruments. They had a great deal of respect for me as an ‘artiste’ … Since I was in very poor health, the French sent me home just four weeks after the end of the war. I first went back to my parents in my home town of Nuremberg, which had suffered terrible damage.”

Post-war years

In the years following the war, Hermann taught and gave lessons in calligraphy in Nuremberg. In 1947, he returned to Frankfurt and took a position with the Stempel AG foundry with little qualification other than his sketch books from the war years.

From 1948 to 1950, while he worked at Stempel on typography designs for metal punch cutting, he developed a specialization in book design. Hermann also continued to teach calligraphy twice a week at the Arts and Crafts School in Offenbach.

It was during these years, that Zapf designed Palatino and Optima. Working closely with the punch cutter August Rosenberg, Hermann design Palatino and named it after the 16th century Italian master of calligraphy Giambattista Palatino. In the Palatino face, Zapf attempted to emulate the forms of the great humanist typographers of the Renaissance.

Optima, on the other hand, expressed more directly the genius of Zapf’s vision and foreshadowed his later contributions. Optima can be described as a hybrid serif-and-sans serif typeface because it blends features of both: serif-less thick and thin strokes with subtle swelling at the terminals that suggest serifs. Zapf designed Optima during a visit to Italy in 1950 when he examined inscriptions at the Basilica di Santa Croce in Florence. It is remarkably modern, yet clearly derived from the Roman monumental capital model.

By the time Optima was released commercially by Stempel AG in 1958, the industry had begun to move away from metal casting methods and into phototypesetting. As many of his most successful fonts were reworked for the new methods, Zapf recognized—perhaps before and more profoundly than most—that phototypesetting was a transitional technology on the path from analog to an entirely new digital typography.

Digital typography

To grasp the significance of Zapf’s work, it is important to understand that, although “cold” photo type was an advance over “hot” metal type, both are analog technologies, i.e. they require the transfer of “master” shapes from manually engraved punches or hand drawn outlines to final production type by way of molds or photomechanical processes.

Due to the inherent limitations of metal and photomechanical media, analog type masters often contain design compromises. Additionally, the reproduction from one master generation to the next has variations and inconsistencies connected with the craftsmanship of punch cutting or outline drawing.

With digital type, the character shapes exist as electronic files that “describe” fonts in mathematical vector outlines or in raster images plotted on an XY coordinate grid. With computer font data, typefaces have many nuances and features that could never be rendered in metal or photo type. Meanwhile, digital font masters can be copied precisely without any quality degradation from one generation to the next.

From the earliest days of computers, Hermann Zapf began advocating for the advancement of digital typography. He argued that type designers needed to take advantage of the possibilities opened up by the new technologies and needed to create types that reflected the age. Zapf also combined knowledge of the rules of good type design with a recognition that fonts needed to be created specifically for electronic displays (at that time CRT-based monitors and televisions).

In 1959, at the age of 41, Zapf wrote in an industry journal, “It is necessary to combine the purpose, the simplicity and the beauty of the types, created as an expression of contemporary industrial society, into one harmonious whole. We should not seek this expression in imitations of the Middle Ages or in revivals of nineteenth century material., as sometimes seems the trend; the question for us is satisfying tomorrow’s requirements and creating types that are a real expression of our time but also represent a logical continuation of the typographic tradition of the western world.”

Warm reception in the US

Despite a very cold response in Germany—his ideas about computerized type were rejected as “unrealistic” by the Technical University in Darmstadt where he was a lecturer and by leading printing industry representatives—Hermann persevered. Beginning in the early 1960s, Zapf delivered a series of lectures in the US that were met with enthusiasm.

For example, a talk he delivered at Harvard University in October 1964 became so popular that it led to an offer for a professorship at the University of Texas in Austin. The governor even also made Hermann an “Honorary Citizen of the State of Texas.” In the end, Zapf turned down the opportunity due to family obligations in Germany.

Among his many digital accomplishments are the following:

-

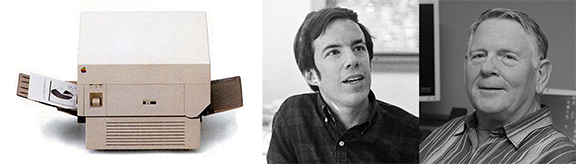

Rudolf Hell When digital typography was born in 1964 with the Digiset system of Rudolf Hell, Hermann Zapf was involved. By the early 1970s, Zapf created some of the first fonts designed specifically for any digital system: Marconi, Edison, and Aurelia.

- In 1976, Hermann was asked to head a professorship in typographic computer programming at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) in Rochester, New York, the first of its kind in the world. Zapf taught at RIT for ten years and was able to develop his conceptions in collaboration with computer scientists and representatives of IBM and Xerox.

-

With Aaron Burns In 1977, Zapf partnered with graphic designers Herb Lubalin and Aaron Burns and founded Design Processing International, Inc. (DPI) in New York City. The firm developed software with menu-driven typesetting features that could be used by non-professionals. The DPI software was focused on automating hyphenation and justification as opposed to the style of type design.

- In 1979, Hermann began a collaboration with Professor Donald Knuth of Stanford University to develop a font that was adaptable for mathematical formulae and symbols.

-

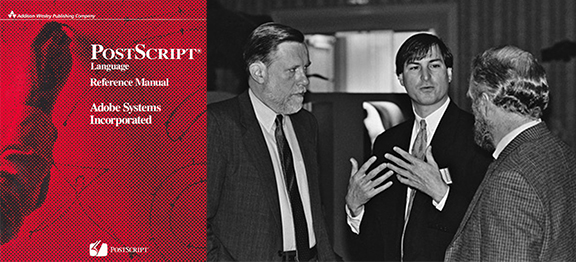

With Peter Karnow In the 1990s, Hermann Zapf continued to focus on the development of professional typesetting algorithms with his “hz -program” in collaboration with Peter Karow of the font company URW. Eventually the Zapf composition engine was incorporated by Adobe Systems into the InDesign desktop publishing software.

Zapf’s legacy

Hermann Zapf actively participated—into his 70s and 80s—in some of the most important developments in type technology of the past fifty years. This was no accident. He possessed both a deep knowledge of the techniques and forms of type history and a unique appreciation for the impact of information technologies on the creation and consumption of the written word.

In 1971, Zapf gave a lecture in Stockholm called “The Electronic Screen and the Book” where he said, “The problem of legibility is as old as the alphabet, for the identification of a letterform is the basis of its practical use. … To produce a clear, readable text that is pleasing to the eye and well arranged has been the primary goal of typography in all the past centuries. With a text made visible on a CRT screen, new factors for legibility are created.”

More than 40 years before the Apple design team set out to create a font that is legible on multiple computer screens, the typography visionary Hermann Zapf was theorizing about the very same questions.