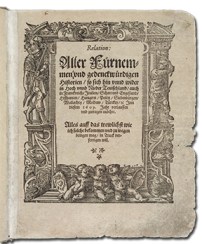

The great cultural movement called the Renaissance (rebirth) spanned the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries. This places Johannes Gutenberg’s 1450 invention of printing early in that era. As is widely acknowledged by historians, printing was not only the most important technological achievement of the Renaissance; it was also its greatest catalyst.

Along with the expansion of world trade and the circumnavigation of the globe—combined with enthusiasm for Gutenberg’s innovation—printing spread rapidly from Germany to destinations across Europe and elsewhere. And, as the business and products of “mechanical writing” proliferated, the knowledge that came along with it multiplied exponentially.

Eventually, like so many printing press pebbles tossed into the global pond, the ripple waves of literacy and democracy spread and connected with one another. By the eighteenth century, the achievements of the Renaissance led to the age of Enlightenment. And so, one of the most remarkable end results of this technical and cultural transformation was the American Revolution of 1776 … but that takes us a long way from the subject of this review.

The Renaissance, especially in Italy, was shaped by humanist teachings, i.e. the notion that citizens should be educated in the humanities (language, literature, philosophy, religion and the arts). Florence, Naples, Rome, Venice and Genoa were among the centers of Italian humanism. Great collections of antique hand written manuscripts and also printed books were assembled in libraries and made available for study primarily for those of wealth and means.

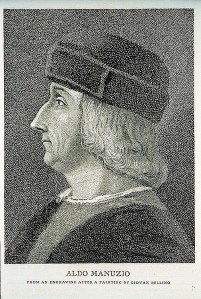

It was within this environment that Aldo Manuzio (Aldus Manutius is Latinized) was born in Bassiano, Italy about 100 kilometers south of Rome. The precise date of his birth is not known. It has been surmised that he was born in 1449 or 1450 from the preface to a book published by Aldus’ grandson, Aldus, The Younger, in 1597.

Very little is known about Aldus’ early life. In his The Rudiments of Latin Grammar published in 1501, Aldus mentions he was trained in Latin at a young age. This information—along with the fact that he had an ancestor that was a Bishop—indicates that his family was well off.

Aldus left Bassiano for Rome, perhaps as young as 15 years of age, to be educated as a humanist scholar. His classical studies in Latin continued in Rome for eight years at which time he moved to Ferrara to conduct studies in Greek. Sometime around 1479 or 1480, having established himself as a scholar of the highest quality, the King of Carpi hired Aldus to become the teacher of his nephews. It was during his time in Carpi that Aldus developed his interest in publishing and printing.

By the 1400s, Venice was a center of world commerce much like New York City might be considered today; everything important was happening there. And so, it was to this Italian center of so many things that Aldus, at the time in his late 30s, decided to relocate and start a publishing enterprise.

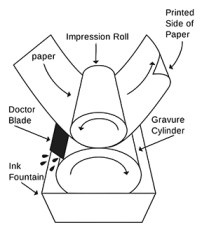

There is almost no information available about Aldus’ activity during his first five years in Venice. It has been deduced that he spent this time preparing and setting up a viable publishing business—learning the book market and printing technique—in a very competitive environment. Printing arrived in Venice by way of Germany twenty years earlier and there were well-known firms already operating by the time Aldus launched his enterprise.

Aldus’ initial activity—and this would prove to be his most important accomplishment—was to edit and republish authoritative editions of the classics of literature. The initial project, a reissue of the Greek Grammar of Constantine Liscaris in 1495, was the first volume to be published under Aldus’ name although Andrea Torresani’s press likely did the printing.

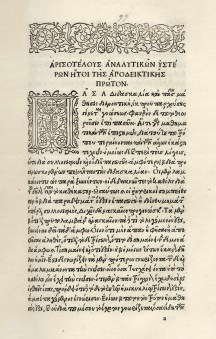

A big breakthrough came in that same year with the publication in Greek of the first of a five-volume folio edition of the works of Aristotle. It would take four years to complete the project. This work has been referred to as the “greatest scholarly and printing achievement of the fifteenth century.” Aldus then went on to edit and publish Thucydides, Sophocles and Herodotus in 1502, Xenophon’s Hellenics and Euripides in 1503 and Demosthenes in 1504. In the decade before his death, Aldus also published editions of Latin and Italian classics.

By 1496, had his own printing operation and began using various forms of “at Aldo’s” to signify the source of his publications as what later became known as the Aldine Press. In 1498, Aldus began using the Aldine Press trademark—the emblem of the dolphin wrapped around the anchor that symbolized the Latin phrase “Festina lente” (Make haste slowly)—on all of his works. At this point Aldus turned his attention to innovations in the forms of print, the first big contribution being in typography.

The typography of print as it arrived from Germany was in the Gothic form of heavy, “gross” lettering as seen in the Gutenberg bible. By 1470, Nicholas Jenson—who had come to Venice from France—had transformed the printed word and created the Renaissance book with his slender roman typeface and capital letters.

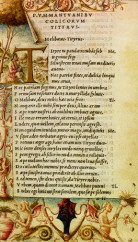

Aldus began with Jenson’s typeface and reworked it into his own style for the Greek classics. His desire was to make the fonts look like the work of human handwriting. This effort would ultimately lead to the development of the “italics” that emulated cursive writing and also became known at times as the Aldino typeface. Francesco Griffo, to whom Aldus later paid tribute, performed the actual artistry of cutting the slanted italic. The first book that contained Aldus’ italic font was the 1501 Aldine Press edition of Virgil’s Opera.

The early period of printing—from 1450 to 1500—is often referred to as the “incunabula” or cradle of printing. At that time, most books were printed in folio format, i.e. page sizes of approximately 14.5” by 20” (the pages in the Gutenberg bible are approximately 17” x 24.5”). These were very large books that could be read wherever they were located; they were not portable.

This is when Aldus made another historic advancement. As explained by Helen Barolini in her Aldus and his Dream Book, “The real revolution, the moment of true divulgation of the printed word that impelled Western society … came when Aldus brought out his edition of Virgil’s Georgics in elegant, octavo format that was to become the staple of the Aldine press and Aldus’ trademark.”

Aldus created the first octavo book.

The octavo format is approximately 7.25” x 10,” something very close to what would be found today in a bookstore. Aldus produced the very first modern book that was small enough and inexpensive enough for someone to take with them almost anywhere.

Aldus’ other innovations included a unique method for bookbinding sometimes referred to as “binding in the Greek style” and advancements in punctuation such as the creation of the semicolon and the modern comma.

Aldus Manutius married Maria, the daughter of Andrea Torresani—the owner of a printing firm with whom he had worked early on in Venice—in 1505. Aldus died on February 6, 1515. His brothers-law took over the Aldine press and ran it until 1533 when Aldus’ third son Paulus Manutius assumed control of the business. It is believed that the Aldine Press published more than 1,000 titles in the hundred years that ended in 1595.

The scholar, humanist, publisher and printer Aldus Manutius was a monumental figure of the Renaissance. He was a force for the expansion of literacy and knowledge for everyone. Fortunately, his books have survived and there is a substantial record of his work including his own words that were often printed in the preface of Aldine Press books. In the Thesaurus Cornucopiae of 1496, Aldus wrote:

“My only consolation is the assurance that my labors are helpful to all … so that even the ‘book-buriers’ are now bringing their books out of their cellars and offering them for sale. This is just what I predicted years ago, when I was not able to get a single copy from anyone on loan, not even for one hour. Now I have got what I wanted: Greek volumes are made available to me from many sources … I do hope that, if there should be people of such spirit that they are against the sharing of literature as a common good, they may either burst of envy, become worn out in wretchedness, or hang themselves.”