Last November Amazon opened its first retail book store in Seattle near the campus of the University of Washington. More than two decades after it pioneered online book sales—and initiated the e-commerce disruption of the retail industry—the $550 billion company seemed to be taking a step backward with its “brick and mortar” Amazon Books.

However, Amazon launched its store concept with a nod to traditional consumer shopping habits, i.e. the ability to “kick the tires.” Amazon knows very well that many customers like to browse the shelves in bookstores and fiddle with electronic gadgets like the Kindle, Fire TV and Echo before they make buying decisions.

So far, the Seattle book store has been successful and Amazon has plans to open more locations. Some unique features of the Amazon.com buying experience have been extended to the book store. Customer star ratings and reviews are posted near book displays; shoppers are encouraged to use the Amazon app and scan bar codes to check prices.

Amazon’s book store initiative was also possibly motivated by the persistence and strength of the print book market. Despite the rapid rise of e-books, print books have shown a resurgence of late. Following a sales decline of 15 million print books in 2013 to just above 500 million units, the past two years have seen an increase to 560 million in 2014 and 570 million in 2015. Meanwhile, the American Booksellers Association reported a substantial increase in independent bookstores over the past five years (1,712 member stores in 2,227 locations in 2015, up from 1,410 in 1,660 locations in 2010).

Print books and e-books

The ratio of e-book to print book sales appears to have leveled off at around 1 to 3. This relationship supports recent public perception surveys and learning studies that show the reading experience and information retention properties of print books are superior to that of e-books.

The reasons for the recent uptick in print sales and the slowing of e-book expansion are complex. Changes in the overall economy, adjustments to bookstore inventory from digital print technologies and the acclimation of consumers to the differences between the two media platforms have created a dynamic and rapidly shifting landscape.

As many analysts have insisted, it is difficult to make any hard and fast predictions about future trends of either segment of the book market. However, two things are clear: (1) the printed book will undergo little further evolution and (2) the e-book is headed for rapid and dramatic innovation.

Amazon launched the e-book revolution in 2007 with the first Kindle device. Although digital books were previously available in various computer file formats and media types like CD-ROMs for decades, e-books connected with Amazon’s Kindle took off in popularity beginning in 2008. The most important technical innovation of the Kindle—and a major factor in its success—was the implementation of the e-paper display.

Distinct from backlit LCD displays on most mobile devices and personal computers, e-paper displays are designed to mimic the appearance of ink on paper. Another important difference is that the energy requirements of e-paper devices are significantly lower than LCD-based systems. Even in later models that offer automatic back lighting for low-light reading conditions, e-paper devices will run for weeks on a single charge while most LCD systems require a recharge in less than 24-hours.

Nick Sheridon and Gyricon

The theory behind the Kindle’s ink-on-paper emulation was originated in the 1970s at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center in California by Nick Sheridon. Sheridon developed his concepts while working to overcome limitations with the displays of the Xerox Alto, the first desktop computer. The early monitors could only be viewed in darkened office environments because of insufficient brightness and contrast.

Sheridon sought to develop a display that could match the contrast and readability of black ink on white paper. Along with his team of engineers at Xerox, Sheridon developed Gyricon, a substrate with thousands of microscopic plastic beads—each of which were half black and half white—suspended in a thin and transparent silicon sheet. Changes in voltage polarity caused either the white or black side of the beads to rotate up and display images and text without backlighting or special ambient light conditions.

After Xerox cancelled the Alto project in the early 1980s, Sheridon took his Gyricon technology in a new direction. By the late 1980s, he was working on methods to manufacture a new digital display system as part of the “paperless office.” As Sheridon explained later, “There was a need for a paper-like electronic display—e-paper! It needed to have as many paper properties as possible, because ink on paper is the ‘perfect display.’”

In 2000, Gyricon LLC was founded as a subsidiary of Xerox to develop commercially viable e-paper products. The startup opened manufacturing facilities in Ann Arbor, Michigan and developed several products including e-signage that utilized Wi-Fi networking to remotely update messaging. Unfortunately, Xerox shut down the entity in 2005 due to financial problems.

Among the challenges Gyricon faced were making a truly paper-like material that had sufficient contrast and resolution while keeping manufacturing costs low. Sheridan maintained that e-paper displays would only be viable economically if units were sold for less than $100 so that “nearly everyone could have one.”

As Sheridon explained in a 2009 interview: “The holy grail of e-paper will be embodied as a cylindrical tube, about 1 centimeter in diameter and 15 to 20 centimeters long, that a person can comfortably carry in his or her pocket. The tube will contain a tightly rolled sheet of e-paper that can be spooled out of a slit in the tube as a flat sheet, for reading, and stored again at the touch of a button. Information will be downloaded—there will be simple user interface—from an overhead satellite, a cell phone network, or an internal memory chip.”

E Ink

By the 1990s competitors began entering the e-paper market. E Ink, founded in 1998 by a group of scientists and engineers from MIT’s Media Lab including Russ Wilcox, developed a concept similar to Sheridon’s. Instead of using rotating beads with white and black hemispheres, E Ink introduced a method of suspending microencapsulated cells filled with both black and white particles in a thin transparent film. Electrical charges to the film caused the black or white particles to rise to the top of the microcapsules and create the appearance of a printed page.

E Ink’s e-paper technology was initially implemented by Sony in 2004 in the first commercially available e-reader called LIBRIe. In 2006, Motorola integrated an E Ink display in its F3 cellular phone. A year later, Amazon included E Ink’s 6-inch display in the first Amazon Kindle which became by far the most popular device of its kind.

Subsequent generations of Kindle devices have integrated E Ink displays with progressively improved contrast, resolution and energy consumption. By 2011, the third generation Kindle included touch screen capability (the original Kindle had an integrated hardware keyboard for input).

The current edition of the Kindle Paperwhite (3rd Generation) combines back lighting and a touch interface with E Ink Carta technology and a resolution of 300 pixels per inch. Many other e-readers such as the Barnes & Noble Nook, the Kobo, the Onyx Boox and the PocketBook also use E Ink products for their displays.

Historical parallel

The quest to replicate, as closely as possible in electronic form, the appearance of ink on paper is logical enough. In the absence of a practical and culturally established form, the new media naturally strives to emulate that which came before it. This process is reminiscent of the evolution of the first printed books. For many decades, print carried over the characteristics of the books that were hand-copied by scribes.

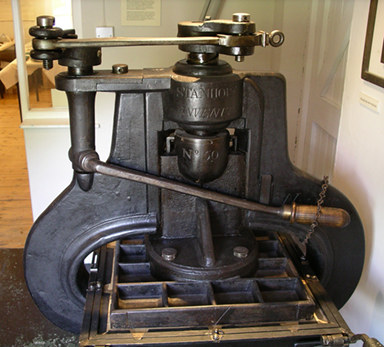

It is well known that Gutenberg’s “mechanized handwriting” invention (1440-50) sought to imitate the best works of the Medieval monks. The Gutenberg Bible, for instance, has two columns of print text while everything else about the volume—paper, size, ornamental drop caps, illustrations, gold leaf accents, binding, etc.—required techniques that preceded the invention of printing. Thus, the initial impact of Gutenberg’s system was an increase in the productivity of book duplication and the displacement of scribes; it would take some time for the implications of the new process to work its way through the function, form and content of books.

More than a half century later—following the spread of Gutenberg’s invention to the rest of Europe—the book began to evolve dramatically and take on attributes specific to printing and other changes taking place in society. For example, by the first decade of the 1500s, books were no longer stationary objects to be read in exclusive libraries and reading rooms of the privileged few. As their cost dropped, editions became more plentiful and literacy expanded, books were being read everywhere and by everybody.

By the middle 1500s, both the form and content of books became transformed. To facilitate their newfound portability, the size of books fell from the folio (14.5” x 20”) to the octavo dimension (7” x 10.5”). By the beginning of the next century, popular literature—the first European novel is widely recognized as Cervantes’ Don Quixote of 1605—supplanted verse and classic texts. New forms of print media developed such as chapbooks, broadsheets and newspapers.

Next generation e-paper

It seems clear that the dominance of LCD displays on computers, mobile and handheld devices is a factor in the persistent affinity of the public for print books. Much of the technology investment and advancement of the past decade—coming from companies such as Apple Computer—has been been committed to computer miniaturization, touch interface and mobility, not the transition from print to electronic media. While first decade e-readers have made important strides, most e-books are still being read on devices that are visually distant from print books, impeding a more substantial migration to the new media.

Additionally, most current e-paper devices have many unpaper-like characteristics such as relatively small size, inflexibility, limited bit-depth and the inability to write ton them. All current model e-paper Kindles, for example, are limited to 6-inch displays with 16 grey levels beneath a heavy and fragile layer of glass and no support for handwriting.

A new generation of e-paper systems is now being developed that overcome many of these limitations. In 2014, Sony released its Digital Paper System (DPT-S1) that is a letter-size e-reader and e-notebook (for $1,100 at launch and currently selling for $799). The DPT-S1 is based on E Ink’s Mobius display, a 13.3” thin film transistor (TFT) platform that is flexible and can accept handwriting from a stylus.

Since it does not have any glass, the new Sony device weighs 12.6 oz or about half of a similar LCD-based tablet. With the addition of stylus-based handwriting capability, the device functions like an electronic notepad and, meanwhile, notes can be written in the margins of e-books and other electronic documents.

These advancements and others show that e-paper is positioned for a renewed surge into things that have yet to be conceived. Once a flat surface can be curved or even folded and then made to transform itself into any image—including a color image—at any time and at very low cost and very low energy consumption, then many things are possible like e-wall paper, e-wrapping paper, e-milk cartons and e-price tags. The possibilities are enormous.