A polymath is a person with extraordinary expertise in multiple disciplines. The most remarkable polymath of all time was Leonardo da Vinci, the Italian Renaissance painter, sculptor, inventor, engineer, musician, astronomer, anatomist, biologist, geologist, cartographer, physicist and architect. In addition to painting the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, Leonardo also conceptualized a flying machine, adding machine, solar power and plate tectonics among many other innovations … in the 16th century.

Any list of polymaths in world history would include:

- Nicolaus Copernicus: astronomer, lawyer, physician, politician and economist

- Isaac Newton: mathematician, physicist, theologian, astronomer and philosopher

- Benjamin Franklin: author, printer, scientist, inventor and statesman

- Thomas Jefferson: architect, paleontologist, inventor, horticulturalist and politician

It goes without saying that people with such a range of talents are extremely rare. Among the distinguishing attributes of a polymath are boundless curiosity and a facility for encyclopedic knowledge. Additionally, because they have the ability to acquire extensive practical experience in overlapping fields, polymaths are often responsible for inventions, discoveries, breakthroughs and noteworthy creative works.

While it would be an exaggeration to place William Morris—a significant figure of the late 19th century—in the company of the above-mentioned geniuses of human achievement, he was nonetheless a polymath. During his lifetime, William Morris made major contributions to architecture, textile design, decorative arts, poetry, literary fiction, politics, typography and printing.

Early years

William Morris was born on March 24, 1834 in Walthamstow. He was the third child and oldest son of William Morris and Emma Morris Shelton. His father, who had moved to London from Worcester in the 1820s, became a partner in a stock brokerage firm in the city. His mother was the daughter of Joseph Shelton, a music teacher in Worcester.

In the early 1840s, the elder William Morris became very wealthy from an investment in a copper mining business. The family then moved into a 150-acre estate in Woodford with its own brewery, bakery and buttery and a Governess and housekeeping staff.

Little William Morris was a precocious child and learned to read very early. By the age of four—it is said—he was reading books and familiarizing himself with the Waverly novels. At Woodford, William spent time exploring the outdoors, going fishing and rabbit hunting and he developed a life-long appreciation for animal nature. After William Morris senior died at age 50 in 1847, the Morris family moved back to Walthamstow along with a considerable fortune.

One year later, William Morris was enrolled at Marlborough College where he attended for three years. In a recollection of his experience at Marlborough, Morris said it was “a new and very rough school. As far as my school instruction went, I think I may fairly say I learned next to nothing there, for indeed next to nothing was being taught.” Despite this negative memory, Morris spent time in the school library and developed an interest in archaeology and gothic architecture. He also took long walks in the countryside amid the Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments, stone circles and burial mounds.

Following a rebellion and four-day strike in 1851 by students against the conditions at Marlborough, the Morris family removed William from the college. Determined to prepare him for entry into Oxford, the family arranged a private classical tutor for the seventeen-year-old William. In 1852, William was admitted as a non-resident and unable to dine or sleep in the company of his fellow students, he entered Exeter College, Oxford.

The Brotherhood

It was at Exeter that William made the acquaintance of a student from Birmingham, Edward Burne-Jones, who would become a lifelong friend and collaborator. While the two students had entered the school with the intention of joining the priesthood, they both decided to dedicate themselves to the arts following a trip and tour of the great Gothic cathedrals in Northern France.

William then joined Edward—along with several other undergraduates and friends of Burne-Jones from Birmingham—in a group of intellectuals that called itself “The Brotherhood.” This club, which historians sometimes call the Birmingham Set, began meeting regularly to read theological tracts. This gave way to Shakespeare, the poetry of Tennyson and Browning, the novels of Dickens and then to a secular study of the art and architecture of the middle ages.

By 1855, the young men were influenced greatly by the views of John Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites who wanted to counter the influence of the industrial revolution upon artistic and cultural expression. Ruskin and his followers believed that art had to be returned to the hand-craftsmanship that had been abandoned beginning with the works of Raphael. Ruskin taught that the separation of the intellectual work of the designer from the manual work of physical construction—a significant feature of mass industrial economy—was socially and esthetically damaging.

Returning to medieval artistic forms and techniques—and rebelling against what was considered the “barbarity” of contemporary industrial culture—would become a recurring theme of the subsequent works of William Morris. He developed the firm conviction that “without dignified, creative human occupation people became disconnected from life.” Alongside these cultural ideas, Morris and “The Brotherhood” advocated social reform aimed at improving the conditions of misery among the industrial workingmen of Victorian England.

In 1856, the members of “The Brotherhood” published twelve monthly issues of the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine—financed by Morris—which espoused the views of the group. It was out of these ideas, that William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones, Charles Faulkner, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and others would establish what later became known as the Arts and Crafts Movement that spread throughout the world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Morris’s accomplishments

It is not possible to deal in detail with the many significant accomplishments made by William Morris in so many fields over the next four decades. The following is a brief listing:

– Architecture:

- He transformed domestic architecture and construction with the Red House built in Kent for Morris and his wife in 1859 with designs by Philip Webb. The house is made of red brick with a steep tiled roof, utilizing all natural materials.

- Morris founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) in 1877 dedicated to the repair and preservation of England’s ancient buildings. The society still exists with 8,500 members and operates according to Morris’s original manifesto.

– Decorative Arts:

- Founded in 1861 Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. for the creation of woodcarvings, stained glass, metalwork, paper hangings, printed fabrics and carpets.

- To this day, the textile designs of William Morris—for furniture, embroidery and wallpaper—remain among the most popular choices for home decor.

– Literature:

- Morris wrote several novels—News From Nowhere (1890), The Wood Beyond the World (1894) and The Well at the World’s End (1896)—that were the first works of science fiction fantasy. Morris influenced both C.S. Lewis (The Chronicles of Narnia) and J. R. R. Tolkien (The Lord of the Rings).

- In 1869, after learning Old Norse language and together with Eirikr Magnusson, Morris published translations of Icelandic mythology and folklore into English. The project eventually became a six-volume library of 9th century Icelandic sagas.

– Politics:

- In 1883, Morris became an active member of the Social Democratic Federation and played a prominent role in its political work.

- Morris was the financier, editor and writer from 1885-1890 for Commonweal an influential English left political magazine.

Kelmscott Press

Toward the end of his life, William Morris turned to the craft of printing and publishing. In 1891, he founded Kelmscott Press along with William Bowden near his home in Hammersmith, London. As with his previous artistic ventures, Morris wanted to shift book design and production back to that of medieval times.

At Kelmscott Press, Morris set out to produce books with traditional methods as much as possible. This meant first of all redesigning typefaces to reflect the look of the fifteenth century and simultaneously eschewing the use of lithographic printing systems. Morris believed strongly that contemporary book production was inferior to that which could be achieved by the craftsmen’s handwork based on strict adherence to fifteenth century techniques.

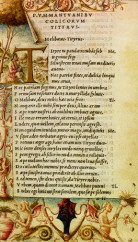

For all 53 books produced by Kelmscott Press, special hand-woven paper was made entirely of linen, natural materials were used for custom-made inks and Morris himself designed the typefaces. Based upon the 1470 type of Nicholas Jenson, Morris developed his Golden type in 1891. Later that year he also designed the gothic Troy font based upon the black letter type printed by Gutenberg in 1450.

Perhaps Morris’s greatest printing accomplishment was The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer published by Kelmscott in 1896. The magnificent volume established a new standard for book design at the end of the 19th century. Adorned with 87 illustrations and many decorative black borders of acanthus and vine—all designed and produced by Morris’s friend Burne-Jones—there were approximately 425 copies printed.

Morris’s contribution to book design was summed up in a talk that he delivered to the Bibliographic Society in 1893 called “The Ideal Book.” In his presentation, Morris exhibited his considerable knowledge of the technology of book printing as well as the esthetics of typographic design. In poetic style, Morris said,

First, the pages must be clear & easy to read; which

they can hardly be unless,

Secondly, the type is well designed; and

Thirdly, whether the margins be small or big, they

must be in due proportion to the page of letter.

William Morris—the polymath designer, author, social theorist and printer—died on October 3, 1896 at the age of 62. A major figure of the late 19th century and during a time of great technological change, Morris sought solutions to the dilemmas of his time in medieval styles and methods. While one may rightfully question his romanticism and identification of industrial progress with “barbarity,” the positive influence of William Morris lives on today in many more ways than is popularly appreciated or understood.