Everyone is familiar with National Geographic magazine. Published monthly and now celebrating its 125th year, National Geographic has a worldwide circulation of more than 8 million copies and appears in thirty-six languages. Widely known for the yellow rectangular border of its cover and the use of dramatic color photographs of world geography, history and culture, it is one the most popular magazines ever printed.

The name National Geographic is used occasionally as a printing industry euphemism. Someone might say, “It’s not National Geographic” when speaking of color reproduction expectations of other projects. What most are unaware of, however, is that National Geographic achieves such beautiful and spectacular color printing largely because of the gravure method used in the printing of its editorial pages.

Although less common in publication printing than offset lithography, gravure printing is typically associated with magazines that have very large circulation. According to Hans Wegner, VP of Production Services at National Geographic, gravure printing provides superior color saturation and consistency, a more photographic look as well as cost advantages.

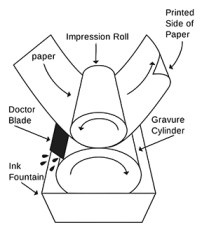

The gravure process—a form of intaglio printing—involves engraving an image carrier, typically a metal cylinder, with recessed cells. The cylinder is immersed and rotates in fluid ink. As the cylinder turns, ink fills the imaging cells and, before making contact with the paper, a doctor blade scrapes the excess ink off the cylinder in the non-image area. The paper is brought into contact with the inked cylinder by an impression roller and the ink is drawn out of the cells onto the paper by capillary action.

The high quality reproduction of gravure printing is the result of the following attributes:

- Very fine halftone dot sizes that emulate the grain of continuous tone photography and can reproduce greater image detail than offset printing.

- A CMYK color gamut than that is often wider than that of offset printing because a greater amount of ink pigment is transferred the surface of the paper.

The history of gravure printing is complex and poorly documented. Dealing with the lack of reliable historical information in his History of Industrial Gravure Printing up to 1920, Otto M. Lilien wrote, “More and more of the technical development is described with only sketchy details and it is noticeable that the references are often missing. Frequently the information contradicts itself regarding the person credited with inventions and technical improvements.”

The manual gravure printing process was created and perfected in the nineteenth century and the earliest inventions are associated with photography. In 1826, Joseph-Niécephore Niépce developed the first photomechanically etched printing plate that was made of zinc and used to print portraits. In 1852, William Henry Fox Talbot developed a method for making gravure printing plates that could transform a continuous tone picture into a halftone.

According to Lilien, Paris publisher Auguste Godchaux took out the first patent for a gravure printing press that used cylinders and printed on a web of paper in France, in 1860. Godchaux built the press and it ran for 80 years in a printing facility in Paris on Boulevard Charonne until the Nazi’s occupied the city in 1940.

Karel Klíč (Karl Klietsch) is the recognized inventor of modern gravure printing. Although it is sometime stated that Klíč developed all of the complex gravure processes without knowledge of the work of others, he was actually the first to bring all of them together. According to Lilien, Klíč brought together the crossline screen and the transfer of gelatine pictures to metal plates for cylinder production.

Karel Vaclav Klíč was born on May 31, 1841 in Hostinne, in the foothills of the Krkonose Mountains in the present-day Czech Republic and about 35 Kilometers from the border with Poland. The town has been known as a center of papermaking.

Klíč showed interest in the arts and at the age of fourteen was admitted to the Art Academy in Prague where he was expelled for nonconformance in 1855. He later returned to complete his studies. As a young man, Klíč worked as a draughtsman, a painter, illustrator and cartoonist. With his latter skills he worked at newspapers in Prague, Brno (Moravia) and Budapest before opening a photographic studio in Vienna, Austria in 1883.

While in Austria, Klíč joined the Photographic Society of Vienna and was exposed to many of the new developments in reproduction methods. His early attempts at photogravure techniques were exhibited with much acclaim at the annual society exhibitions in 1879 and 1880. During these years, Klíč did not reveal anything publicly about his methods. Recognizing the monetary value of the process he had perfected, Klíč sold the process to others in Vienna and London.

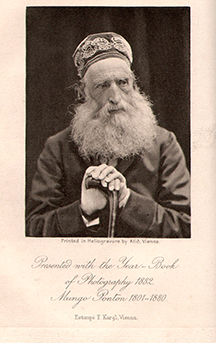

In 1880 and 1881, several of Klíč’s photos were published in an Austrian journal Photography Correspondence. In 1882 a heliogravure portrait of Mungo Ponton—a Scottish pioneer in photographic techniques and an amateur scientist—was reproduced as a special insert to the British The Yearbook of Photography and Photographic News Almanac.

Writing about the significance of the image of Ponton, the editor of the almanac wrote, “We ought to say a word about our portrait of Mungo-Ponton, an Englishman who may well be termed the discoverer of permanent photographic printing, for he it was who proposed, in 1839, the employment of bichromate in photography. Klic’s is an etching process upon copper, an imprint from a carbon diapositive being secured upon that metal. The mode of preparing the copper is a secret, but we may mention that the process is so quick, that within four or five days an engraved plate may be produced of considerable dimensions. Of the quality of the printing our readers can judge for themselves. Suffice it to say, the process is an inexpensive one, and that during the past year alone, no less than three hundred photo-engravings were produced.”

After one of his business associates by the name of Leonard published the details of his process in an Austrian technical journal in March 1886, Klíč left the country in frustration and traveled to England. It was during this trip that Klíč came into contact with Samuel Fawcett, a process worker at the Storey Brothers, a calico-printing firm located in Lancaster.

It is known that Klíč’s vision for gravure reproduction extended beyond single sheet photographic prints. Fawcett had been working independently in 1890 on a series of gravure experiments and his contact with Klíč was the catalyst for the development of entirely new industrial printing system.

Klíč and Fawcett, beginning in 1895 with formation of the Rembrandt Intaglio Printing Company, jointly developed the rotogravure process—modern gravure printing. The men experimented with screens of 150 and 175 lines per inch and printing on paper with machines owned by Storey Brothers and designed for printing on textiles.

The process developed by the Rembrandt Intaglio Printing Company remained secret for ten years, giving the firm lucrative monopoly on the process before any competitors emerged in the market. In 1897, while technical director of the company, Klíč left England and returned to Vienna to continue with further experimentation and invention. He came back for a short time in 1906 after he perfected a method for three-color gravure process with fine halftone screens. Karel Klíč died in Vienna on November 16, 1926.