Color is a perception; it is the response of the human visual system to light reflected from objects in the world around us. We learn as children to associate these color perceptions with names: the red of an apple, the green of the leaves or the blue of the sky. More scientifically, color is the way our eyes, optic nerve and brain receive and process different wavelengths of the visible spectrum of electromagnetic radiation.

It took hundreds of years of thought and experiment—beginning with Isaac Newton’s 1672 idea that white light is the source of color sensation—to arrive at the modern understanding of color and the way we perceive it. In 1802, the visible spectrum of electromagnetic energy was defined by Thomas Young when he measured various wavelengths of light and established their relationship to color, i.e. red is about 650 nm, green is about 510 nm and blue is about 475 nm.

Later, Young and Hermann von Helmholtz developed the theory of trichromatic color vision. They surmised that the human eye has three types of photoreceptors, each with particular sensitivity to a corresponding range of light waves. In the 1950s it was proved—with advanced measuring equipment—that the three kinds of visual receptors (cones) have the capacity to sense many combinations of light wavelengths and see them as all the colors of the rainbow.

Knowledge of the properties of light and color was a major achievement of the scientific revolution (1500 to 1900) that—alongside the discovery of graphical perspective and other mathematical linear projections—transformed the visual arts. Artists and craftsmen that exclusively relied on their sensibility, talent and experience were able to integrate the principles of science into their works, bringing a degree of realism and accuracy that was previously impossible.

While the history of two-dimensional color representation is most often associated with fine art painting—the fresco, oil and tempera works of the Renaissance masters—the lesser known origins of color printing took a parallel development in time. Starting with the birth of mechanical metal type in Germany during the High Renaissance, a quest was begun to conquer the challenge of practical and high-quality color printing.

Relief color, Fust and Schoeffer (1457)

There is evidence that Johannes Gutenberg experimented with color during the printing of his famous 42-line Bible. For the most part, however, traditional hand-painted ornamental color lettering was used by Gutenberg alongside the black letter printing type he invented around 1450. Shortly thereafter, relief printing of color type and other ornamental figures was performed remarkably well by Gutenberg’s former collaborators on the printing of the Bible, Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer.

In 1457, Fust and Schoeffer printed the Mainz Psalter with three colors—black, red and blue—all at one time. Their ingenious technique of compound printing involved interlocking metal type characters that were inked separately and reassembled for a single impression on the printing press. Although it returned extraordinary results, the process was very time consuming and expensive.

Intaglio color, Teyler ( 1680)

For most of the next two centuries, limited color printing was attempted as hand-colored pages remained the preferred method of pictorial representation. As various printing techniques spread across Europe, new approaches to color reproduction were tested. Some color illustrations were made using wood blocks.

By the mid-fifteenth century, intaglio engraving emerged as the standard method for printing images in black and white. Around 1680, a mathematician and engineer from Nijmegen, Holland named Johan Teyler developed a means of dabbing different colored inks into the wells of intaglio plates—originally intended for black-only printing—to make a full-color impression all at one time. Like Fust and Schoeffer’s work, Teyler’s color results were artistically beautiful but could not be developed into a viable commercial process.

Three-color mezzotint, Le Blon (1720)

Following the publication in 1704 of Isaac Newton’s discoveries regarding the physics of light and color—especially the idea that all colors are made of different combinations of red, blue and yellow (this was later proven to be imprecise for both light waves and pigments)—a few printers began working with techniques in three-color mezzotint printing. By this time, mezzotint copperplates were the favored image reproduction method because they rendered tones more easily than engraving.

In 1711, the Frankfurt-born painter Jacob Christoph Le Blon, basing himself directly upon Newton’s theory, mastered trichromatic mezzotint printing in his Amsterdam studio. Le Blon first tried and failed to commercialize his invention in Amsterdam, The Hague and Paris. He relocated in London in 1720, successfully obtained a royal patent from George I for his process and opened up a business selling printed color copies of oil paintings.

While his technical accomplishment was a significant step forward, Le Blon’s business lasted for three years before bankruptcy forced him back to Paris. Creating an appropriate balance of intensity between the primary color plates and maintaining tight registration between the three press impressions upon the paper was an exceedingly difficult and costly trial-and-error process.

Four-color mezzotint, L’Admiral and Gautier (1736)

It is documented that J. C. Le Blon also invented four-color mezzotint printing by adding black to the red, yellow and blue plates on a few of his prints. However, the perfection RYBK (K is for the key color, black) model was made by others, especially following Le Blon’s death in 1741. Among those who contributed were the Dutch engraver and printer Jan L’Admiral and the French painter Jacques Gautier, who had both been assistants to Le Blon. L’Admiral and Gautier initially produced color plates of human anatomy for medical research publications in Paris in the 1730s and 1740s.

In France, Gautier proved to be something of a charlatan and attempted to take full credit for the invention of four-color printing. He started a periodical in 1752 called Observations on natural history, on physics and painting in which popular sensationalism appears to have been his primary objective. Gautier fabricated a full-color image of a “siren” with the body of a seahorse and a hideous head of a human and reproduced some images that bordered on pornography. Nonetheless, Gautier’s journal proved to be among the first financially successful uses of color printing; it was published quarterly for five years.

Chromolithography, Engelmann (1837)

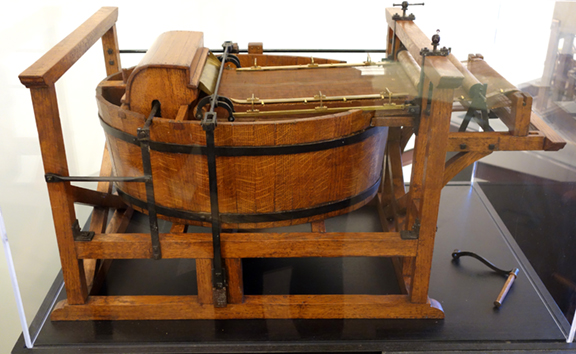

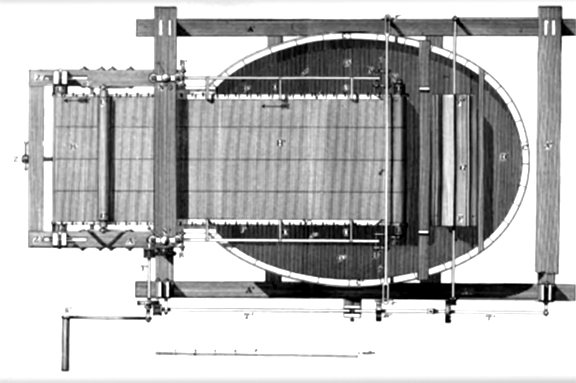

The invention of lithography by the Bavarian Alois Senefelder in 1796 brought a fundamentally new approach to printing. While relief letter press and intaglio mezzotint were mechanical printing processes, lithography relied upon the chemical antipathy of oil and water to transfer the image onto paper. The new method enabled artists to draw on the surface of limestone instead of the much more difficult etching or engraving of metal plates. In 1818, Senefelder experimented with lithographic color reproduction and pointed the way forward for others.

For the next two decades, lithographers from Germany, France and England made strides with color, for the most part printing decorative ornamentations or title pages of relief printed books. The chromolithography during this time was also a return to a multi-color approach of the seventeenth century as opposed to the later and more advanced three- or four-color mezzotint separation process.

Chromolithography came of age with the work of the French-German Godefroy Engelmann of Mulhouse. After becoming a pioneer and master in monochrome lithography, Engelmann made significant progress with four-color lithographs in 1837. He moved to Paris a year later and obtained a patent for his process. His works proved that chromolithography could effectively render lifelike prints of landscapes, flower and fruit arrangements and the most difficult human forms.

Toward modern color printing

The four-color chromolithography of the mid-nineteenth century finally brought color printing to an economically viable balance of quality, time and cost. However, full color printing was still largely a special process that was performed separately from letterpress black-only text print. With the rapid industrial expansion of book and newspaper publishing, color work remained essentially a very slow, craft-based process that required highly skilled artisans.

The production of relief, intaglio and lithographic “prints” and “plates” remained the convention for color work during the balance of the 1800s. These products were most often sold as single items—sometimes for as little a penny each—or bound into books as illustrations. It would require the development and maturity of three major advancements in the graphic arts to integrate printed color together with black text: color photography by Thomas Sutton (1861) and halftone reproduction by Frederic Ives (1881) and the CMYK ink model (1906).

Initially, some black and white halftones were enhanced with synthetically applied color. By the 1920s, improvements in mechanical color separation techniques and the growth of magazine publishing made it possible for some titles to afford full-color pictures and black text to be printed together on sheetfed letterpress systems. Some of these publications, such as National Geographic Magazine, continued with letterpress color all the way up to the late 1970s.

By the late 1950s, offset lithography and electronic color separations had begun their rise as the foremost method of reproducing high quality, inexpensive printed color images. Although the personal computer (IBM, 1981), digital camera (Fuji, 1987) and digital printing (Indigo, 1993) have brought color reproduction to new levels of high quality and low cost—especially for small quantities—the breakthroughs of seventy years ago remain by far the dominant methods of color reproduction today.