Last September, NAPL (National Association for Printing Leadership) published a valuable eleventh edition of a report called “State of the Industry.” The report provides a multi-faceted and insightful look into the condition of the printing industry—the changes, challenges and opportunities faced by printing firms today—based upon a survey of executives and owners from more than 300 companies.

Last September, NAPL (National Association for Printing Leadership) published a valuable eleventh edition of a report called “State of the Industry.” The report provides a multi-faceted and insightful look into the condition of the printing industry—the changes, challenges and opportunities faced by printing firms today—based upon a survey of executives and owners from more than 300 companies.

The report is the work of Andrew Paparozzi, NAPL Chief Economist, and Joseph Vincenzino, NAPL Senior Economist. The NAPL economists overlay the survey results upon other general information to develop a depth of understanding about the dynamic forces impacting the industry. A copy of the report is available for NAPL members at no charge and non-members can purchase it on the NAPL web site for $149.95. http://members.napl.org/store_product.asp?prodid=369

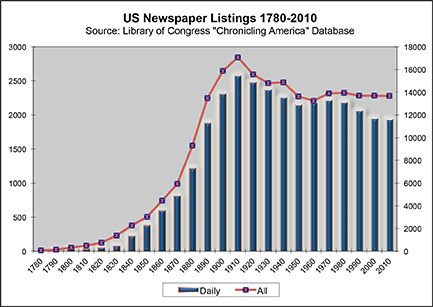

A central theme of the survey results and analysis—both quantitative and qualitative—is that print is undergoing a transformation of historic magnitude. The difficulties created by the Great Recession of 2008-2009 that caused business volumes to fall dramatically—and they still remain today some 21% below pre-recession highs—are but one side of the problems created by rapidly evolving print markets.

The report begins with the following: “Business remains a tough grind, with little opportunity for organic growth.” This means that firms competing for “new” business are struggling over a traditional print market pie that is getting smaller; and yet market redistribution is also underway because of the second side of the changing business climate: the fundamental adjustments brought on by digital communications technologies and methods.

As Paparozzi and Vincenzino explain in the Executive Summary, “Getting and staying on the right side of market redistribution is the most significant challenge for everyone in our industry. Market redistribution is structural, not just cyclical. So much of what’s happening in our industry is the result of digitization, the Internet, and profound change in how people communicate, not GDP. Consequently, we have fewer printers but more competition—we’re in a constant battle for market share.”

The NAPL analysis is more than a review and commentary on the condition of the industry (Chapters: “Where We Are” and “Where We Are Headed”); the report also contains an assessment of those firms that are doing well in the current environment. It brings together generalizations (Chapters: “What We Have to Do” and “We May Need to Look Elsewhere”) about the correct way to approach the printing business today (Chapters: “Leaders: A Diverse Group” and “Ideas for Action”). At the same time, the report cautions against any kind of formulaic or “cookie-cutter” solution for every company or situation.

As the Executive Summary concludes: “It isn’t enough to know what’s happening and what’s ahead. We have to act on what we know—a game plan for action—taking steps to make the upheaval redefining our industry an opportunity rather than a threat. This report provides several ‘ideas for action’ to do just that.” These actions are summarized as “Hear the voice of our clients more clearly; execute more efficiently and successfully; communicate company direction to employees more effectively; and cultivate new skills across our organization.”

Macro trends

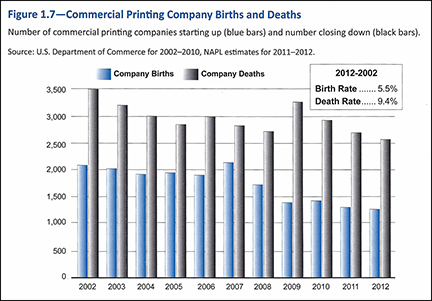

One interesting point that is made deals with the contraction of the industry. It is well know that the number of printing establishments has been declining for the last two decades; since 1992 there were 16,000 fewer companies in the industry (41,012 down to 25,242) by 2012. However, as the report analyses, not only are companies dying off, but there are also new firms being born each year.

What kind of companies are these businesses? NAPL answers thus: “These companies are coming in with a clean slate—i.e. without legacy equipment, work habits and mindsets that limit flexibility or the troublesome issue of long-term, loyal employees whose skills don’t match the direction in which the company is embarking. Rather they are hiring the skills they at the start, creating a workforce with talents more relevant to our new industry. That they tend to be smaller companies shouldn’t create a false sense of security: Smaller companies grow—and the good ones grow rapidly.”

Another important point the report makes about the overall situation is that a boost in overall economic activity as reflected in GDP is not going to produce a “recovery” in printing. In any event, the very modest economic growth remains lackluster because of “headwinds” such as government cutbacks and the implications of the Affordable Care Act.

NAPL predicts that US printing industry sales will rise .5%-1.5% in 2013 and as much as 1.0%-3.0% in 2014 following an increase of .6% in 2012. While these figures are very modest, the report shows that these results are not projected to be even across all regions of the country. While some regions, such as South Central, have experienced double-digit growth since 2007, others like the Southeast and North Central have seen an overall decline of -.5%.

Print business priorities

The NAPL survey results reveal what company owners and executives consider the most important areas of focus and how they approach them. The following are the business topics and the top responses to the survey:

- Hearing the Voice of the Customer

Meeting more frequently on an owner-to-owner/executive-to-executive basis (64%) - Client Education

We offer client education programs and materials (56.4%) - Employee Communications

One-on-one or small group meetings (77%) - Execution issues

Poor follow through. Start off well, but lose focus (39.8%) - Strategic Shifts

We will no longer carry unproductive employees (48.3%) - Critical Skills

Sales (71.3%) - What We’d Most Like to Upgrade

Web-to-print, web storefront, ecommerce (51%)

One of the striking results of the survey is that there is an expanding divergence between industry leaders and the rest of the industry. This comes out most obviously on the sales front. It is clear from the foregoing data that understanding customer needs, business development and sales are a top priorities for printing company owners and executives.

In an environment of intense competition, differentiation is key to winning and retaining clients. In order to survive and grow, those companies that have been most successful have absorbed the meaning of the fundamental changes taking place and are offering a complex array of products and services beyond ink on paper. As summed up in the comment of one survey participant, “Successful printers recognize they are part of the communications industry, not the printing industry.”

Where does offset lithography fit?

An important aspect of the NAPL report deals with the state of traditional offset printing. In fact, the report contains a page following the executive summary called, “What About Lithography?” which makes some highly valuable comments about the relationship between the old and the new of the industry.

Offset lithography is still the single biggest source of revenue in the printing industry. At between $40 and $45 billion, this market breaks down as follows:

- Advertising print: $10.2 billion

- Magazine/periodical print: $4.9 billion

- Catalog/directory print: $3.2 billion

- Miscellaneous other print: $20 billion

Eighty-eight percent of NAPL survey respondents reported that they get one quarter of their revenue from offset lithography and 70% report that it accounts for at least half. Printing companies cannot afford to “walk away” from this dominant yet traditional source of revenue. “Put simply, once we won by being the best lithographer. Now we win by being the best at putting lithography and every other service that we offer—it’s print-and, not print-or—to work for our clients.” This is a very good summary of where we are as an industry: one foot in the old and one foot in the new era of communications.